It begins, as so many things do, with a confession. To admit that marketing is about influencing human behaviour—“Marketing is about influencing human behaviour”, as Holly Pound of Depop puts it—is, in certain circles, rather like declaring a secret fondness for cheesy rom-coms and obscure jazz. One is met with knowing glances, a raised eyebrow, perhaps even a sigh. Yet this is the world we inhabit: a society in which the art of persuasion has become less the province of snake-oil salesmen and more the daily occupation of well-heeled professionals with PowerPoint decks, fMRI scans, and a penchant for the Oxford comm.

Marketing is about influencing human behaviour” — Holly Pound of Depop puts it, a confession that sets the tone for the entire discourse.

The neuroscience gold rush

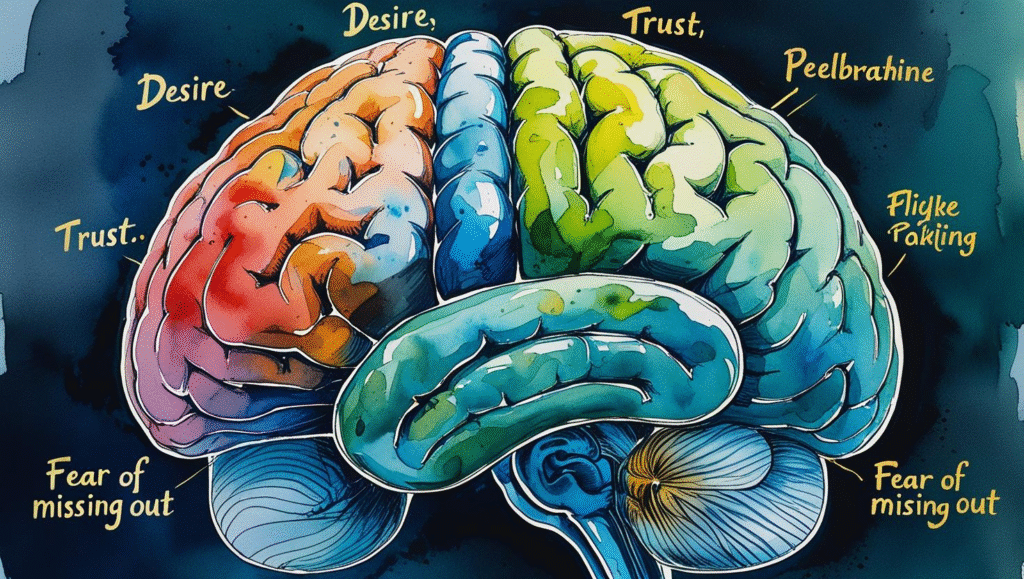

The modern marketer, a curious hybrid of amateur neuroscientist and corporate dramaturge, now perambulates the corridors of commerce with the quiet confidence of someone who knows which neural buttons to press. The tools are impressive—eye-tracking software, A/B tests, the occasional algorithmic séance. The results, at times, are quietly terrifying. One recalls the study in which test subjects, presented with Coca-Cola and Pepsi in blind tastings, showed little neural preference. Introduce the brand labels, however, and the emotional centres of the brain illuminated like Piccadilly Circus at dusk.

Branding, it seems, is less about logos and more about the subtle rewiring of desire.

It would be tempting, at this juncture, to sound the alarm—surely this is the end of free will, the triumph of manipulation over autonomy. But to do so would be to miss the more interesting story: that the very same psychological insights which fuelled our cynicism might, in the right hands, become the foundation for a more civilised, even humane, marketing practice.

The cognitive bias buffet

Modern marketing is a veritable grand tour of cognitive biases, each one meticulously catalogued and, one suspects, weaponised.

The anchoring effect—where the first price encountered becomes the reference point for all subsequent judgements—explains why the “Short” size at Starbucks exists not for consumption but calibration. Loss aversion, that ancient evolutionary hangover, is the engine behind every “limited time offer” and “only three left in stock” message. The scarcity principle, meanwhile, ensures that our shopping baskets are filled with items we neither need nor particularly want, but which might, in some imagined future, become objects of regret if left un-purchased.

“Social proof, that most primal of psychological triggers, now manifests in the digital realm as a parade of customer reviews, star ratings, and the slightly sinister notification that ‘73 people are looking at this item right now.’”

One is reminded of the philosopher’s observation that hell is other people—though in this case, hell is other people’s purchasing decisions.

The generation that refuses to play

Enter Generation Z, a cohort that regards marketing with the wary scepticism of a cat presented with a new brand of food.

Raised on a diet of algorithmic recommendation and influencer fatigue, they have developed what researchers, with characteristic understatement, call “informed scepticism”—distrust paired with active verification. Seventy-two percent investigate brand claims before making a purchase; nearly half are unmoved by the blandishments of paid partnerships.

“Many describe paid partnerships as ‘very insincere’ or ‘annoying,’ expressing a preference for ‘normal people with normal incomes and lives.’” The irony, delicious and not lost on observers, is that a generation raised on social media has become the most immune to its charms. Only 28 percent trust the brands they patronise, a figure that would cause most Victorian shopkeepers to reach for the smelling salts.

The privacy paradox and the personalisation trap

Here, the narrative takes a more subtle turn. Today’s consumer, it seems, is a bundle of contradictions: demanding personalised experiences while expressing mounting concern about privacy. A recent study found that 79 percent of internet users are uneasy about how companies collect and use their data. Yet these same individuals expect recommendations that border on the clairvoyant, provided, of course, that no one mentions the mind-reading part.

“This creates what one might call the ‘personalisation paradox’—consumers want brands to know them without actually knowing them.”

Brands, ever resourceful, have responded with a kind of plausible deniability. They must appear psychic while maintaining the fiction that they are merely very good at guessing. It is a delicate dance, reminiscent of the Victorian parlour game in which everyone knows the secret but pretends not to.

The dark arts of digital manipulation

The digital bazaar has given rise to what researchers, with admirable candour, call “dark patterns”—design elements crafted to nudge, prod, and, on occasion, outright bamboozle the user.

From the mildly annoying (the newsletter sign-up that refuses to be dismissed) to the genuinely Machiavellian (the subscription service that renders cancellation a feat worthy of Theseus), these tactics exploit the quirks of human cognition with the precision of a Swiss watch and the subtlety of a brick through a window.

The effectiveness of these techniques, it must be said, is not distributed evenly. Research suggests that those with less education are more susceptible to manipulation, a fact that raises uncomfortable ethical questions. The industry, for its part, has responded with a variety of codes and guidelines, though these often feel like asking foxes to draft the rules for henhouse security.

The authenticity arms race

In response to growing consumer scepticism, brands have embarked on what might be called an “authenticity arms race.” The word appears in 86 percent of marketing materials, which is, in itself, a kind of paradox.

Authenticity, by its very nature, cannot be strategic. The moment it is, it ceases to be authentic.

Modern consumers, particularly the aforementioned Gen Z, have developed a finely tuned ability to detect manufactured sincerity at twenty paces. The result is a cycle in which brands try ever harder to out-authentic one another, while consumers grow ever more cynical about the entire enterprise.

The ethical tightrope

One arrives, inevitably, at the question of ethics. When does influence become manipulation? Where is the line between helpful nudging and exploitative coercion? Traditional frameworks suggest that marketing should be transparent, create genuine value, and respect autonomy. Yet the most effective psychological techniques often work precisely because they operate below the level of conscious awareness.

“Asking marketers to be transparent about their psychological techniques is rather like asking magicians to explain their tricks—it rather defeats the purpose.”

The industry’s response—statements of ethics, codes of conduct—often feels like a polite fiction, maintained for the benefit of regulators and the easily scandalised.

The fatigue factor

Perhaps the most interesting development in recent years is the emergence of “marketing fatigue.” Consumers, bombarded by a constant barrage of persuasion, are developing mental ad-blockers. The more sophisticated the techniques, the less effective they become. It is, if one is being uncharitable, a kind of arms race in which both sides are losing.

Brands shout ever louder into a void of consumer indifference, like a street preacher at rush hour—earnest, ignored, and slightly hoarse.

The behavioural economics bonanza

Academic research has provided marketers with an entire arsenal of behavioural economics principles. The “paradox of choice” explains why too many options lead to paralysis. The “cheerleader effect” demonstrates how individual items become more attractive when presented in groups. Loss aversion, again, shows why “don’t lose out” messaging outperforms “gain this benefit” appeals. Companies like Netflix and Amazon have built empires on these insights, their algorithms less recommendation engines than engines of desire.

The sophistication of these systems would be genuinely impressive if they weren’t so focused on separating people from their money with maximum efficiency. It’s like watching a master chef prepare a meal, except the meal is your bank account and you’re the one being consumed.

The future of psychological manipulation

Looking ahead, the convergence of artificial intelligence and behavioural psychology promises to make current techniques look positively quaint. AI-powered personalisation systems now adapt messaging in real time; voice-activated devices and augmented reality interfaces create new opportunities for influence. The challenge, if one can call it that, is that consumers are becoming more sophisticated at roughly the same pace as the techniques designed to influence them. It is an evolutionary arms race, with each side developing new defences and countermeasures in perpetual cycle.

The industry speaks breathlessly about “ethical AI” and “responsible personalisation,” terms that sound rather like “compassionate capitalism” or “friendly fire”—oxymorons dressed up in corporate speak. The reality is that any system designed to influence behaviour operates in an ethical grey area by definition.

The curious case of informed resistance

Perhaps the most fascinating development is the emergence of what researchers call “informed resistance”—consumers who understand psychological marketing techniques and consciously resist them. These individuals represent a new category of consumer: the psychologically literate sceptic who shops with the wariness of someone navigating a minefield.

This creates an interesting dynamic where marketing psychology must evolve to counter consumer psychology education. It’s rather like the relationship between computer viruses and antivirus software—an endless cycle of attack and defence. The more consumers learn about manipulation techniques, the more sophisticated those techniques must become to remain effective.

“The ultimate irony is that the most psychologically sophisticated consumers may actually be the most vulnerable to truly advanced manipulation techniques, precisely because they believe themselves to be immune. It’s a kind of marketing equivalent of the Dunning-Kruger effect in reverse.”

In the end, the psychology of marketing represents humanity’s remarkable capacity for self-awareness paired with its equally remarkable capacity for self-deception. We’ve created systems that understand human behaviour better than humans understand themselves, then act surprised when those systems shape behaviour in unexpected ways.

The question isn’t whether marketing psychology works—the evidence is overwhelming that it does. The question is whether we’re comfortable living in a world where our desires are increasingly the product of sophisticated psychological engineering rather than our own choices. Holly Pound’s insight that “marketing is about influencing human behaviour” may be honest, but honesty doesn’t necessarily make it any less unsettling.

Perhaps the real psychology at work here is our collective ability to recognise manipulation whilst simultaneously embracing it, like smokers who read the health warnings whilst lighting up. We know the game is rigged, but we keep playing anyway.

After all, where else would we shop?

References:

- Receptiviti, “Revolutionize Market Research by Understanding Audience Psychology,” 2024. Insights into audience psychology and motivations, including how psycholinguistic analysis can reveal the “why” behind consumer behaviour.

- “An exploration of cognitive bias in marketing decision-making,” All Multidisciplinary Journal, July 2024. A comprehensive review of cognitive biases such as anchoring and loss aversion and their implications for marketing strategies.

- Rajiv Gopinath, “Gen Z and the Rise of Brand Skepticism,” May 2025. Analysis of Gen Z’s sophisticated “informed scepticism” and their approach to brand trust, transparency, and advertising.

- Fortune, “How brands can solve the personalization and privacy paradox,” October 2024. Data and analysis on the tension between consumers’ desire for personalisation and their concerns about data privacy.

- Jamie Luguri & Lior Jacob Strahilevitz, “Shining a Light on Dark Patterns,” Journal of Legal Analysis, March 2021. A study of manipulative digital design patterns and their impact on consumer behaviour and consent.

- Joseph Nunes, Andrea Ordanini, Gaia Giambastiani, “The Concept of Authenticity: What it Means to Consumers,” Journal of Marketing. Research on how consumers define and assess authenticity in brands and products.

- The BLU Group, “Psychological Insights to Improve Marketing,” May 2020. Practical applications of psychological principles in marketing communications and digital content.

- USC MAPP Online, “What Is Consumer Psychology?” November 2023. Overview of consumer psychology and its influence on marketing campaigns and behavioural change.