India’s AI healthcare moment looks, on the surface, like the marketer’s dream brief. A massive, under‑served population. A national story about “open” digital infrastructure. A new family of Google health‑AI models with a name that sounds like it was designed for a medical drama: MedGemma.developers.google+3

Now there’s a YouTube film – “How is AI helping doctors focus on patient care? #HealthierTogether” – that stitches all of this together in under seven minutes. The piece looks beautiful and lands emotionally. It’s also a masterclass in how a single brand film can quietly reposition a research model as health infrastructure, redefine “open”, and make the patient almost disappear.[youtube][research]

For anyone working in tech or health marketing, this isn’t just a neat case study to bookmark for later. It’s a warning label – the kind that should sit next to your next “AI for good” campaign brief, alongside the questions you’re already asking about authenticity and trust in AI‑led storytelling.[linkedin]

Why this film, and why now?

Inside Google, MedGemma is not a side quest. The model family sits on top of Google’s Gemma 3 architecture and targets medical text and image comprehension. Both the technical report and the model card frame MedGemma as a foundation model for developers and researchers, intended to accelerate health‑AI applications – not as a drop‑in diagnostic engine.deepmind+4

Meanwhile, India’s digital story has moved from “fast‑growing market” to “co‑author of digital public infrastructure”: UPI for payments, ONDC for commerce, the Ayushman Bharat Digital Mission for health records. Google understandably wants MedGemma to sit in that slipstream – as the AI engine that plugs into India’s “open ecosystem standards” and underpins a new generation of health tools.

This film lands precisely at that intersection. It wraps a developer‑oriented model in the language of national potential, clinical empathy, and open standards. When you’ve been tracking Google’s broader narrative shifts in advertising and AI, the pattern feels familiar: infrastructure plus emotion, with the business model humming quietly in the background.

The question is not whether the storytelling is clever – it clearly is. The real issue is what this move does to how marketers frame AI in critical sectors like healthcare, and what gets smoothed over in the process.

1. From case film to infrastructure strategy

The film opens, not with a product, but with a claim about identity:

“Every morning I’m reminded of what India really is. Young, restless, and full of potential.”

India, not MedGemma, takes the lead role. The “villain” is cast at system scale:

- A “large and diverse population” that’s both challenge and strength.

- AIIMS Delhi seeing 15,000 patients a day, with clinicians trying to skim records, labs, and images in minutes.

- A skewed doctor–patient ratio, with clinicians concentrated in cities and patients “somewhere very far away in India.”

Within two minutes, the film drops MedGemma into this landscape as an invisible layer that changes what happens in those few minutes with a doctor.

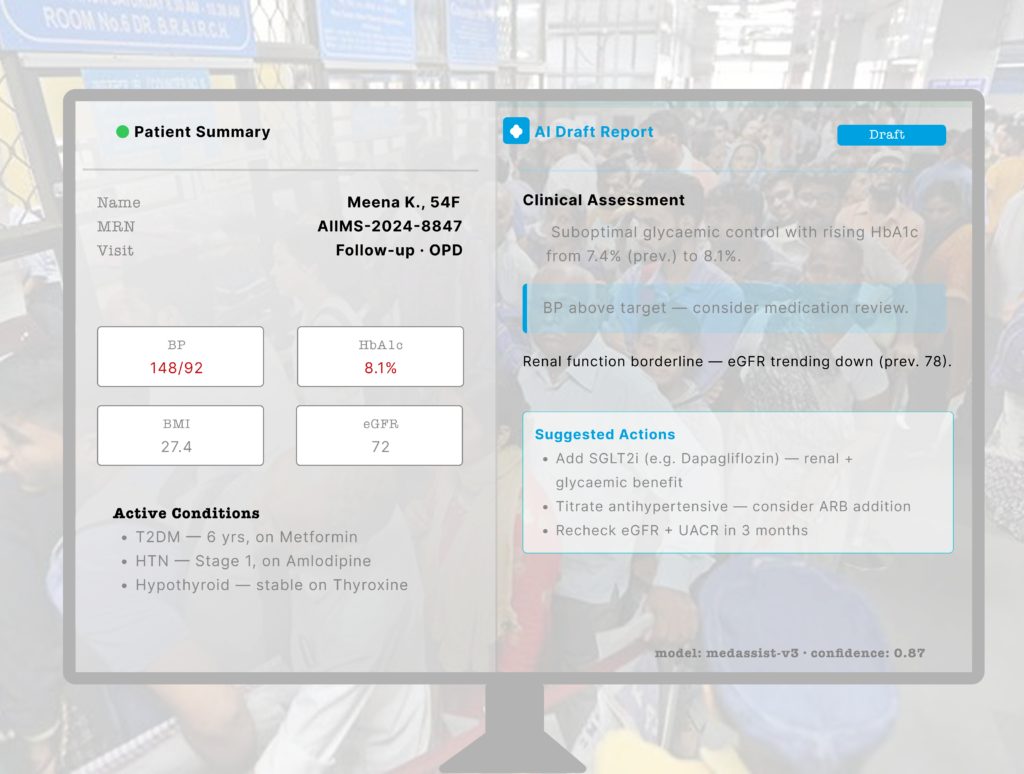

Viewers see:[youtube]

- An AI assistant pre‑collecting patient information before the consult.

- A model doing image classification, interpretation, and report generation.

- A “collaborating centre” at AIIMS convening universities, industry, and startups “specifically directed at AI in healthcare.”

The vocabulary leans hard on infrastructure:

- “Multiple centres across the country.”

- “Open ecosystem standards for industries such as payments, health.”

- “Innovation at scale.”

This is more than a case film. It works as a soft pitch for MedGemma as a future health plumbing layer – the kind of invisible capability that every clinician will eventually touch. If you’ve been following my breakdowns of Google’s broader strategy, that echo with search, Android and UPI‑style narratives then it is hard to miss.[linkedin][youtube]

What the fine print actually says

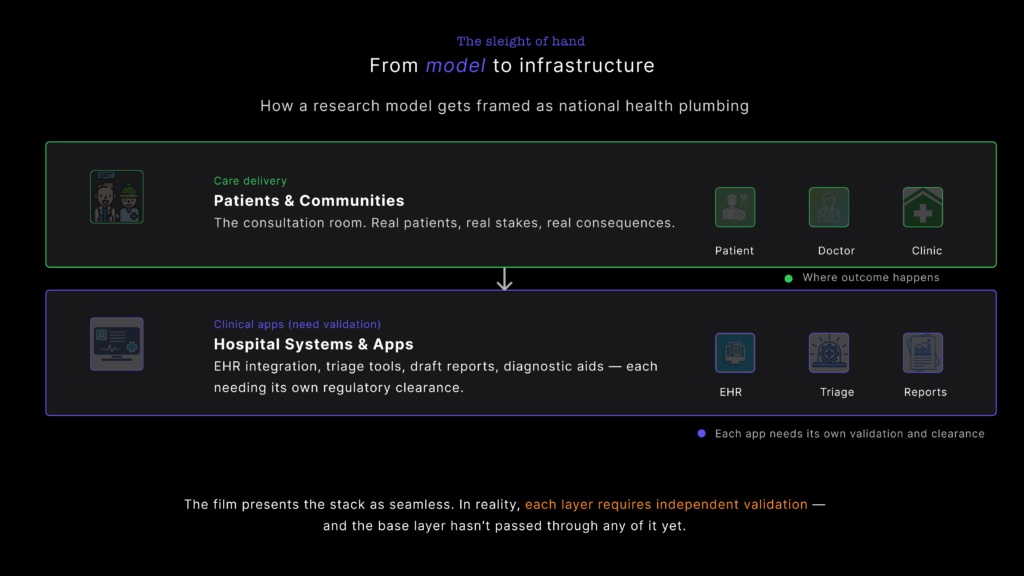

Tilt the camera away from YouTube to the MedGemma model cards. The documentation describes MedGemma as “a collection of medical vision‑language foundation models” based on Gemma 3, and a “starting point that enables more efficient development of downstream healthcare applications.”

The intended‑use section strips away any cinematic gloss: MedGemma “is not intended to be used without appropriate validation, adaptation and/or making meaningful modification by developers for their specific use case.” The outputs “are not intended to directly inform clinical diagnosis, patient management decisions, treatment recommendations, or any other direct clinical practice applications.” All outputs “should be considered preliminary and require independent verification, clinical correlation, and further investigation through established research and development methodologies.”

Meanwhile, the technical report reads exactly like you’d expect a research paper to read: benchmark performance, dataset summaries, ablations, and a focus on improving tools for developers, not on replacing doctors or remaking national health systems overnight.

On screen, though, MedGemma looks and feels like an emerging layer of national infrastructure already embedded into the doctor–patient encounter (film link).

From a marketing perspective, that tension matters: a film that implies “this is how doctors at AIIMS work now” will collide with documentation that tells developers not to use MedGemma directly for clinical decisions. Storylines that position a model as infrastructure also inherit infrastructure‑level responsibilities for clarity, consent, and governance – not just clever cinematography. It’s a familiar gap in AI‑first campaigns: the promise lives at the infrastructure layer; the risk sits in the footnotes (model card).

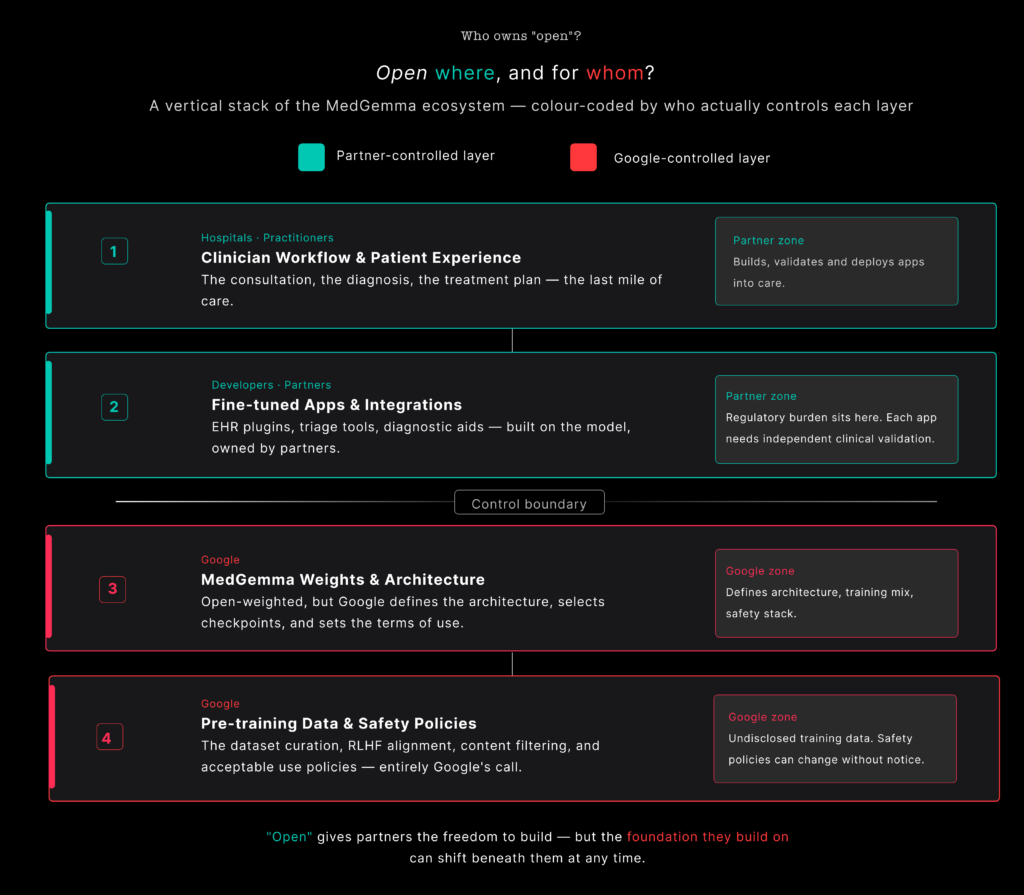

2. Who owns “open” in open medical AI?

One of the most seductive lines in the film sounds innocuous:

“MedGemma is a collection of open models… a starting point available to developers and partners to train and customise in their own way… hosted in their own secure environments.”

That phrase – “open models, hosted in your secure environment” – hits three anxieties in one breath:

- Fear of black‑box AI.

- Fear of sending sensitive data to foreign clouds.

- Fear of being locked into a single vendor’s stack.

It also dovetails neatly with India’s own language of “open ecosystem standards” in payments and health.

The trouble is that “open” is doing more rhetorical work here than technical.

Open… inside a very specific stack

The MedGemma docs tell a more constrained story, which the model card reinforce

- MedGemma builds on Gemma 3, Google’s decoder‑only transformer architecture; Google defines the model design, from tokenisation through context length and optimisation, as detailed in the MedGemma Technical Report (PDF) and the arXiv version.

- Vision capabilities rely on a medically tuned image encoder (MedSigLIP), derived from SigLIP and designed by Google to feed into the same stack, as described in the technical report.

- Pre‑training draws on a mix of public and proprietary datasets, including de‑identified medical images and text. Model cards and technical reports list families of datasets and highlight data‑contamination risks, but downstream teams don’t get full control over or visibility into the pre‑training mix (model card, technical report).

- Models ship through Google‑controlled channels and come wrapped in specific licences and usage terms, for example via Model Garden / docs, google/medgemma-1.5-4b-it on Hugging Face, and the Google‑Health/medgemma GitHub repo.

In practice, “open” means:

- Developers can download weights.

- Teams can fine‑tune those weights.

- Hospitals or partners can host the models in their own infrastructure.

At the same time, Google controls:

- The core architecture and its evolution.

- The original training data blend and its blind spots.

- The safety frameworks, evaluation protocols and red‑teaming methodology.

- The roadmap: new versions, deprecations, ecosystem tooling.

Plenty of other foundation models work this way, so none of this is unusual. The issue lies in how easily viewers can conflate:

- “Open models” in the film – which, in the context of India’s DPI story, sounds suspiciously like public, neutral infrastructure.

- “Open‑weight models under a private vendor’s technical and governance umbrella” in reality.

Why it matters to get “open” right

When a campaign borrows the language of UPI and ABDM, it borrows legitimacy from systems that ultimately answer to public institutions – for example, UPI’s public‑sector governance and ABDM’s official mandate, or broader coverage of India’s digital public infrastructure.

UPI can be reshaped by the RBI and NPCI, not by one company. ABDM’s core registries sit under India’s health ministry. In theory, their design and governance can be contested in Parliament and by civil society.

MedGemma has no similar governance structure outside Google and its immediate partners. The model can be pulled, relicensed or reshaped unilaterally. Its architecture, data mix and safety policies do not go through a democratic process, as even Google’s own MedGemma blog makes clear by framing decisions around internal research and product roadmaps.

That doesn’t make MedGemma “bad”. It just means that marketers need to be precise. If a model is open‑weight, say that. If training or safety is locked inside a private stack, say that too.

You can still align with public infrastructure, but with more nuance:

- “We’re releasing open‑weight models that plug into India’s open health standards, under transparent terms of use.”

- “Hospitals can run these models in their own environments, under their security policies, instead of sending data to our cloud by default.”

- “Here’s the part of the stack we control (architecture, pre‑training, safety frameworks), and here’s what partners control (fine‑tuning, deployment, clinical validation).”

Clarity on who owns what in “open” AI will age better than any hero shot of a data centre. It also helps avoid the dynamic I’ve unpacked in other analyses of Google’s AI narrative – shiny language up front, and concentrated control once you read the footnotes – for instance in this critique of Google’s advertising panic and CPC crisis.

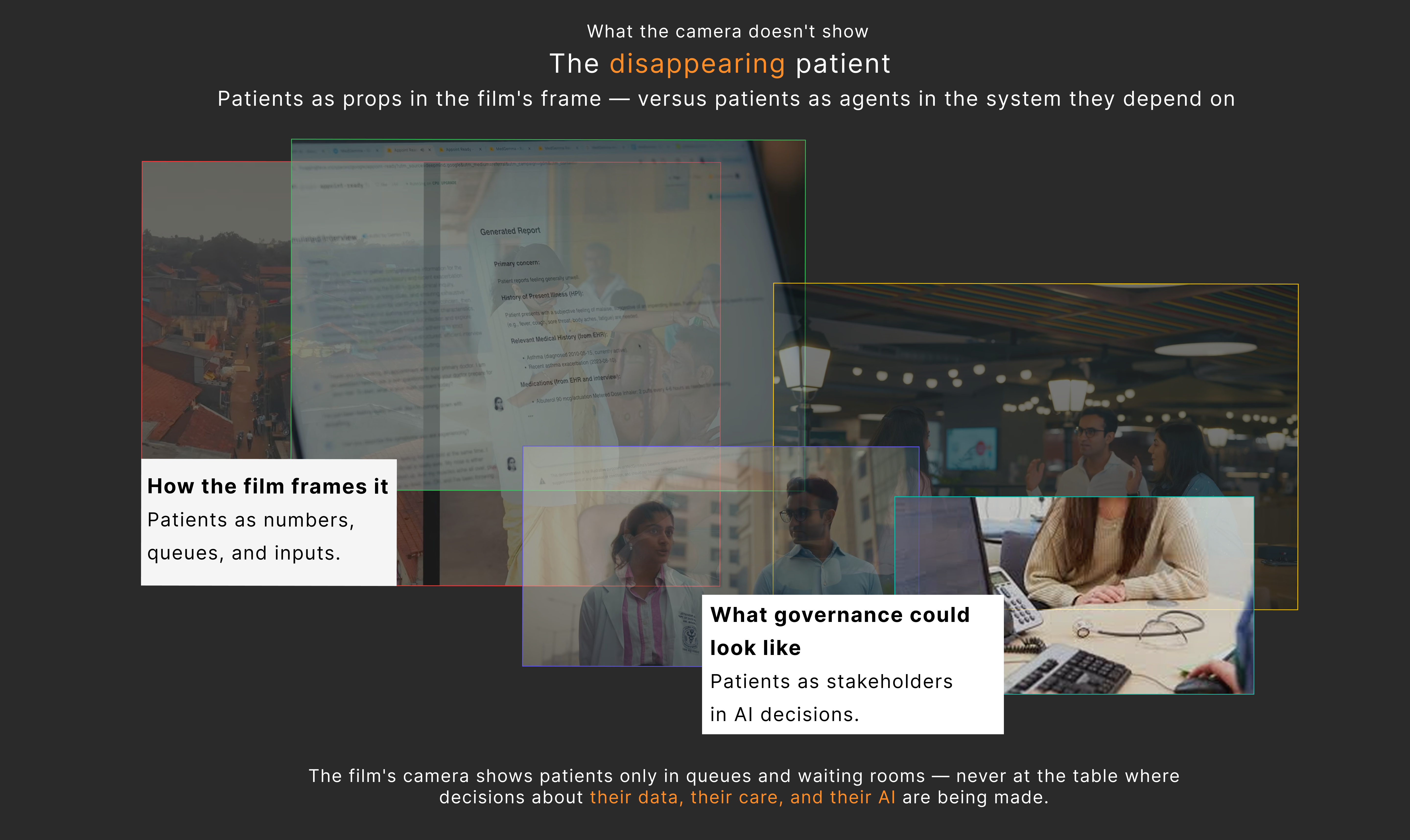

3. The disappearing patient

The film insists that AI’s promise is to “help clinicians do their jobs in ways that allow them to spend more time with patients”, and that the “benefits of technology seep all the way through and actually reach the patient.”[youtube]

Scrub through the script, though, and patients mostly show up in three ways:

- As mass: 15,000 people a day, long queues, “somewhere very far away in India.”

- As inputs: a patient answering an AI assistant’s questions; radiology images flowing into a classifier; reports appearing.

- As abstractions: “the patient” as the end point of innovation, invoked but rarely allowed to speak.

A real patient voice never appears. Nobody asks how it feels to be screened by an assistant, or whether patients want AI in this part of the journey at all. We don’t see what happens when an AI‑drafted report clashes with a clinician’s judgement, or how that conflict gets resolved.

The core relationship on screen looks like this:

- Google ↔ AIIMS (and, by extension, other elite institutions).

Patients sit behind them as justification, not as stakeholders in the design or deployment of the system.

Documentation quietly reinforces this hierarchy

Turn back to the model cards and technical report and that same hierarchy shows up in textual form in the MedGemma documentation and the detailed model card.

Safety and harm evaluation revolves around policy categories: child safety, content safety, representational harms and general medical harms, all spelled out in the model card’s safety section. Evaluation focuses on benchmarks, internal red‑teaming and expert review.

Limitations mention the risk of bias in validation data and data contamination in pre‑training, which the technical report and its HTML version both highlight in their discussion of data sources, contamination checks and evaluation constraints.

These are valuable and more transparent than many AI launches in other sectors. At the same time, there is no mention of:

- Patient advisory councils or community input into evaluation.

- Consent models for downstream tools powered by MedGemma.

- Rights to explanation, challenge, or opting out of AI‑mediated workflows.

From the documentation’s point of view, the patient appears as a risk vector and an eventual beneficiary, not as a decision‑maker. The film inherits that blind spot and acts it out visually.

If you’ve been following my work on AI video authenticity and the “trust penalty” of synthetic content, the pattern should feel familiar: the people whose lives are most affected by AI show up as data points and examples, not as co‑authors of the story, as I argued in this piece on AI video authenticity.

For marketers, this is the place to resist the easy version of the brief. When a campaign claims “AI is a great leveller”, the storytelling needs to do more than pan across a waiting room. Let patients speak. Let them ask uncomfortable questions. Let them say no.

Challenges and ethical considerations you can’t cut around

The film does at least gesture towards risk. It mentions de‑identified datasets, secure environments, and repeatedly calls MedGemma an “assistant”. But if you plan to borrow this narrative shape in your own AI work, three issues deserve more airtime than a single line of VO.

Data privacy and security: who sees what, where?

“Secure environments” and “de‑identified anonymised medical datasets” sound reassuring in a script (film link). In practice, privacy and security in medical AI involve several layers, as even the MedGemma Technical Report and its full text make clear when they discuss data sources, de‑identification and contamination risks.

- Training data provenance: De‑identification reduces risk, but doesn’t erase it. Researchers have demonstrated re‑identification attacks on medical images and clinical text, especially when datasets are combined or linked.

- Access control in deployment: A “secure environment” at a well‑funded academic medical centre looks very different to a server room in a district hospital. The same model can carry different risks depending on who runs it and how they log, audit and restrict access.

- Secondary use creep: Once you have AI‑ready pipelines, data becomes attractive for all kinds of secondary use – analytics, insurance risk scoring, targeted outreach. If marketing stays silent on that, audiences may assume consent where none exists.

For any AI marketed as infrastructure, the story needs to show where data flows, who controls it and what protections exist. That needs to show up in the narrative itself – ideally through clinicians and patients, not just product leads and legal boilerplate.

Algorithmic bias: whose body is the model trained on?

MedGemma’s technical report openly acknowledges limitations and highlights the need for diverse training and evaluation datasets, both in the main technical paper and in extended discussions of data and evaluation in the HTML and PDF versions. Model cards warn developers to validate downstream applications on data “representative of the intended use setting” and flag risks of bias in validation data and contamination in pre‑training.arxiv+2

None of that complexity appears in the film. Bias never gets mentioned. In healthcare, that’s not an abstract fairness problem; it’s a clinical and political one, as coverage of MedGemma in India’s health context keeps hinting at when it talks about access and equity.[biovoicenews]

Certain groups may be more likely to receive mis‑diagnoses if models under‑represent their physiology or disease patterns.

Imaging performance can vary with equipment, phenotype, and disease prevalence.

Triage systems can skew against particular regions, languages, or socio‑economic profiles if the training or evaluation data misses them.

A film that celebrates how patients “somewhere very far away in India” might finally get quality care via AI also needs to show that someone is asking: “Does this model actually perform equally well for them?”

A braver version of this story would let a clinician say:

“We know models can be biased. We’re testing MedGemma on Indian datasets, and here’s one gap we found – plus how we’re addressing it.”

In other campaign analyses – from Google India’s DigiKavach to AI‑powered ads – I keep coming back to the same point: admitting what you don’t know is often more persuasive than pretending the hard problems have vanished, as I argued in this breakdown of Google’s advertising panic and CPC crisis.[linkedin]

Human oversight: assistant, or quiet authority?

The film leans hard on a familiar reassurance. AI is there to “help clinicians”, taking over summarisation, report drafting and classification so doctors can spend more time with patients (film link, overview on AI in healthcare). Model cards echo this by warning developers not to use MedGemma as a substitute for professional judgement and insisting on appropriate clinical oversight.

The problem is that “human in the loop” can mean very different things in real workflows:

- A generated report becomes the default, and the human edits at the margins.

- A classifier’s score anchors the clinician’s assessment, especially for junior staff.

- Time pressure makes it harder to question or override AI outputs, even when a clinician has doubts, as real‑world studies of AI‑mediated care hint at (example of collaboration and pressure in practice).

So the real questions for anyone marketing an AI assistant look more like these:

- How much time does a clinician actually have to disagree with the model in a typical session?

- What training do they receive on when and how to override its suggestions?

- Does the institutional culture back them up when they push back against an AI‑generated output?

Campaigns that promise AI will “free up time” should also acknowledge that digital tools have often been used to increase throughput and documentation, not deep, relational care (example on burnout and workload, AI and workload discussion).

A responsible 2026‑era narrative doesn’t pretend this tension doesn’t exist. Instead it sounds more like:

“We think this will free up time – and here’s how we’re designing the workflow so it doesn’t just become another reason to squeeze more patients into each hour.”

So what should marketers do differently?

If you’re a marketer, strategist, or UX writer working around AI in high‑stakes domains, there’s a lot to learn from this film – and just as much to resist.

1. Treat the model card as part of your script

Before you write a single line of film dialogue or landing‑page copy, treat your model card and technical report as non‑negotiable sources, starting with documents like the MedGemma Technical Report and its full‑text version.

Then:

- Pull key constraints into the narrative itself. What the model cannot do is as important as what it can.

- Let characters voice those limits – a doctor saying, “This doesn’t replace our judgement; it gives us a second lens,” will travel further than a legal disclaimer.

- Show how those constraints play out in practice: approvals, audits, fallback pathways when the model fails.

This isn’t just good ethics. In a landscape where AI promises are cheap, grounded constraints are a competitive advantage.

2. Be precise about “open”

When a model is open‑weight but governed by a proprietary licence, say that. When training relies partly on proprietary data, say that as well.

You can still align with public infrastructure, but with more nuance:

- “We’re releasing open‑weight models that plug into India’s open health standards, under transparent terms of use.”

- “Hospitals can run these models in their own environments, under their security policies, instead of sending data to our cloud by default.”

- “Here’s the part of the stack we control (architecture, pre‑training, safety frameworks), and here’s what partners control (fine‑tuning, deployment, clinical validation).”

Clarity on who owns what in “open” AI will age better than any sweeping claim about democratising healthcare. It also helps avoid the trust erosion we’ve already seen in other AI‑heavy narratives, as I argued in my breakdown of Google’s AI and CPC strategy in Google’s Advertising Panic Reveals CPC Crisis.

3. Put patients back at the centre – for real

If patients are the reason you say you’re doing this, they need to be more than B‑roll. That means:

- Letting them speak about how AI‑enabled workflows actually feel.

- Showing consent conversations, not just consultation footage.

- Including moments where they opt out, or challenge decisions.

Beyond the story, bring patient involvement into the product process:

- Establish patient advisory councils for health AI deployments.

- Publish performance results across regions and demographics.

- Provide clear, patient‑facing documentation and routes to contest AI‑influenced decisions.

A lot of my recent work on agentic AI journeys has focused on turning users from targets into participants (example here). In healthcare, patients are the ultimate “agents”. Campaigns that treat them as such will feel very different to stories where they remain faceless queues in a corridor.

The opportunity – and the risk – in MedGemma‑style stories

Google’s MedGemma film is a skilful piece of narrative engineering. It (watch the film):

- Elevates a developer tool into a symbol of national health infrastructure.

- Reframes “open models” inside a Google‑defined stack as part of India’s public‑infra success story, echoing how MedGemma is presented as an open model family and how Gemma itself is positioned as foundational Google infrastructure.

- Centres elite institutions and technologists while patients hover at the edges (again, visible throughout the film).

For marketers, the temptation is to copy the template: sweeping national stakes, humble but brilliant protagonists, AI as invisible helper.

A smarter move is to treat it as a starting point – and then push past it.

Because the next wave of AI health stories will be judged not just on their cinematography, but on whether they:

- Accurately reflect model capabilities and limits.

- Are honest about who owns what in “open” AI.

- Treat patients as participants in governance, not statistics in a deck.

- Address privacy, bias, and human oversight as design problems, not boilerplate.

Campaigns that can hit those notes won’t just have a beautiful case film. They’ll produce work that clinicians can stand behind, regulators can live with, and patients might actually trust – the same standard we’ll need to hold AI storytelling to across sectors, from search and advertising to the next wave of “AI‑powered” brand campaigns you break down on your own site, as in your critique of Google’s Advertising Panic and CPC crisis.

Footnotes

- How is AI helping doctors focus on patient care? #HealthierTogether[youtube]

- MedGemma | Health AI Developer Foundations [developers.google]

- MedGemma 1.5 model card | Health AI Developer Foundations [developers.google]

- MedGemma Technical Report[arxiv]

- MedGemma Technical Report (HTML version)[arxiv]

- MedGemma – Google DeepMind[deepmind]

- google/medgemma-1.5-4b-it – Hugging Face[huggingface]

- google/medgemma-27b-it – Hugging Face[huggingface]

- google/medgemma-4b-pt – Hugging Face[huggingface]

- Google-Health/medgemma – GitHub[github]

- MedGemma: Our most capable open models for health AI development[research]

- Next generation medical image interpretation with MedGemma 1.5 and medical speech-to-text with MedASR[research]

- From Seed to Scale: Partnering with India’s Startups to Build the AI Future[blog]

- Google announces new additions to its Gemma open model family to advance AI in healthcare in India[biovoicenews]

- Google partners with NHA to deploy AI to digitise medical records[business-standard]

- How AI Is Used in Healthcare – Cleveland Clinic[health.clevelandclinic]

- How AI improves physician and nurse collaboration – Stanford Medicine[med.stanford]

- Introducing MedGemma: Google’s open models for medical AI[infoq]

- Google’s open MedGemma AI models could transform healthcare[artificialintelligence-news]

- AI Video Authenticity – LinkedIn post by Suchetana Bauri[linkedin]

- Google’s Advertising Panic Reveals CPC Crisis – LinkedIn post by Suchetana Bauri[linkedin]

- How Google India’s DigiKavach campaign succeeded and failed – LinkedIn post by Suchetana Bauri[linkedin]

- Agentic commerce and AI agents – LinkedIn post by Suchetana Bauri[linkedin]