The Stranger Things finale isn’t just a television event. It is a case study in how the world’s most functional utility is trying to rebrand itself as a fan club.

January 2026 has officially arrived. The dust is finally settling on Hawkins. Although the Stranger Things finale has landed, dragging a decade of 80s nostalgia, synth-heavy dread, and waffle iconography across the finish line, the real story isn’t just on TV. While Netflix is busy counting the viewing minutes, something fascinating is happening on the other side of the browser tab.

Google has spent the last few weeks turning its search engine into a virtual extension of the Upside Down. Through a pair of videos released just before the New Year—“Plan Your Stranger Things Watch Party” and “Bonus Search Trends”—the tech giant isn’t just riding the coattails of a pop culture juggernaut. Instead, it is making a very specific, very expensive argument about its own future.

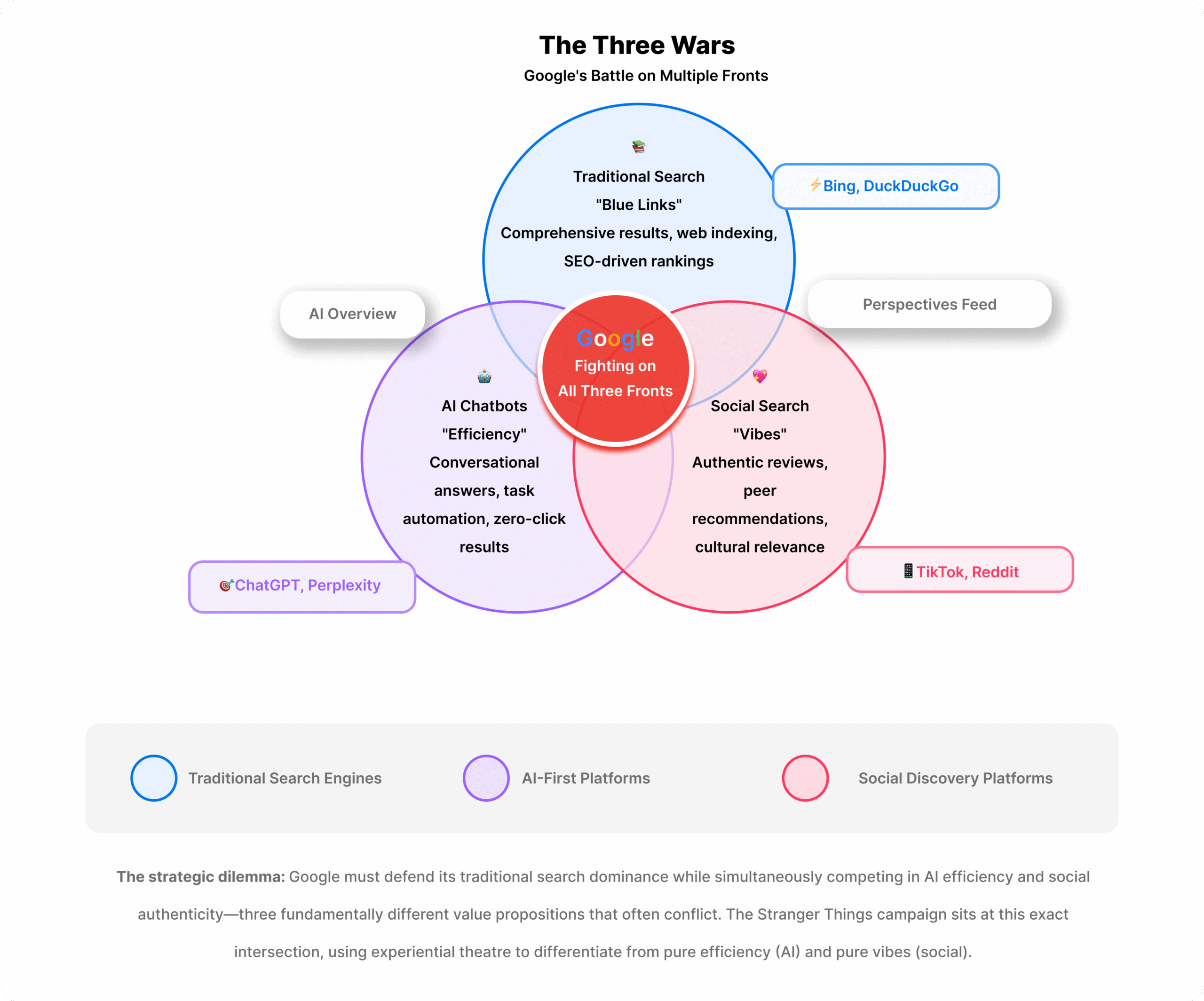

For the past few years, we have been told that Search is dying, or at least facing a crisis of relevance. We are told that Gen Z prefers TikTok for discovery, or that AI chatbots will replace the blue link.

Consequently, Google’s response is not just to be faster or smarter. It is to be more fun. It wants to be the place where the fandom lives.

This campaign is not really about a TV show.

Rather, it is about the “Spotify-ification” of Search—the pivot from organising information to curating emotion.

And for marketers, it offers a masterclass in manufactured spectacle—turning a functional product into a cultural playground.

Let’s dismantle it.

Part I: The Nudge (Or, How to Hack a Habit)

The first piece of creative—a snappy 31-second spot titled Plan Your Stranger Things Watch Party with Google—is deceptive. On the surface, it appears to be a throwaway gag reel. You get the hits: “Friends don’t lie,” the Demogorgon, and the excessive calorie counts of 80s junk food. It is bright, fast, and engineered to trigger the dopamine hit of recognition.

But look closer at the mechanism.

Crucially, the video does not ask you to subscribe to anything. Nor does it ask you to buy a Pixel phone. It has one single, explicit instruction: Search “stranger things”.

This is a classic “behavioural nudge”. Google knows that millions of people will inevitably search for the show anyway—to check release times, to find cast interviews, or to look up recap videos. By explicitly inviting you to do it, they are claiming ownership of that impulse.

Effectively,Google is reframing a utilitarian reflex (finding information) as a participatory act (joining the party).

The UX as Theatre

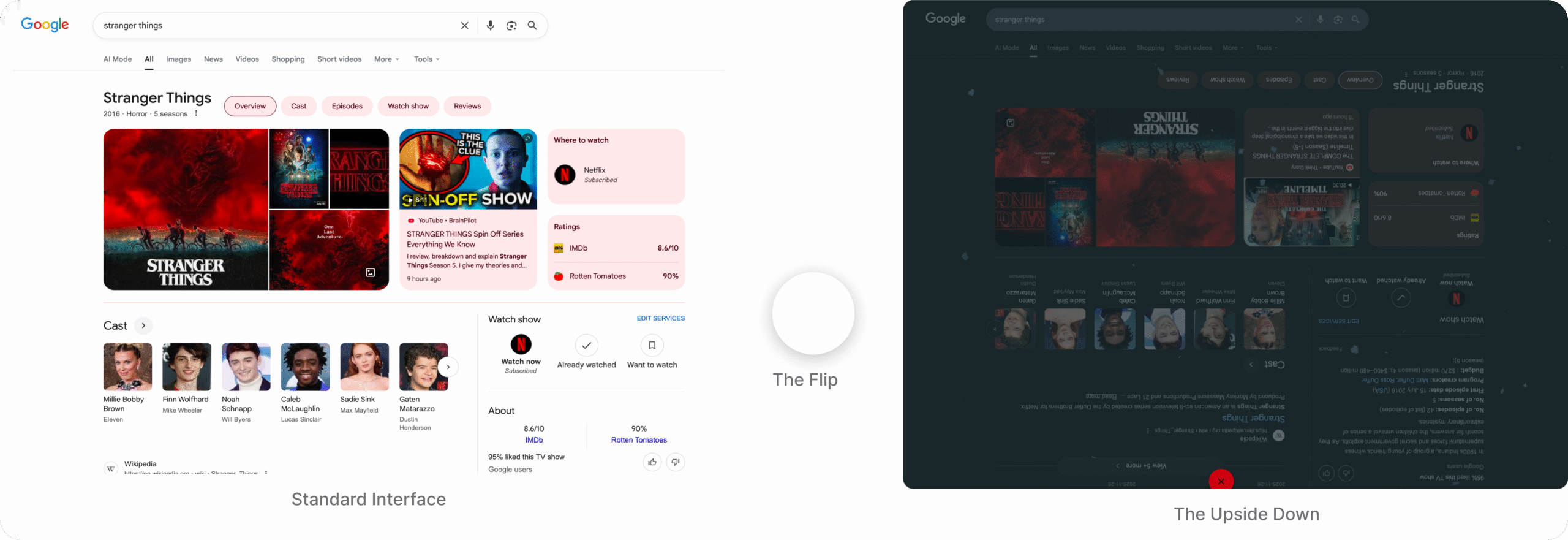

When you actually follow the instruction, the payoff is substantial. We are not just talking about a Knowledge Graph panel with a few cast photos. We are talking about “interface theatre”.

Reports from the launch describe an Easter egg where a dice appears on the screen. If you click it, the entire browser window flips. The white background goes dark; ash-like particles float across the screen; the text inverts. Suddenly, you are in the Upside Down.

Essentially, this is UX design deployed as marketing. It reminds me of the Barbie campaign from a couple of years ago, where the screen turned pink. However, this feels more aggressive. It disrupts the sanctity of the results page.

For a few seconds, the tool that you use to file your taxes or find a plumber becomes a toy.

Why does this shift matter? Because Google is fighting a war on two fronts. On one side, it has the AI answer engines—driven by conversational AI user experiences—which promise efficiency. On the other, it has social search (TikTok, Instagram), which promises vibes.

Consequently, by turning the results page into a theatrical set, Google is trying to prove it can do vibes too. It is saying: “We are not just a librarian. We are part of the culture.”

Part II: Quantified Nostalgia

If the 30-second spot is the hook, the 8-minute mini-documentary—Bonus Search Trends: Stranger Things in Search—is the anchor.

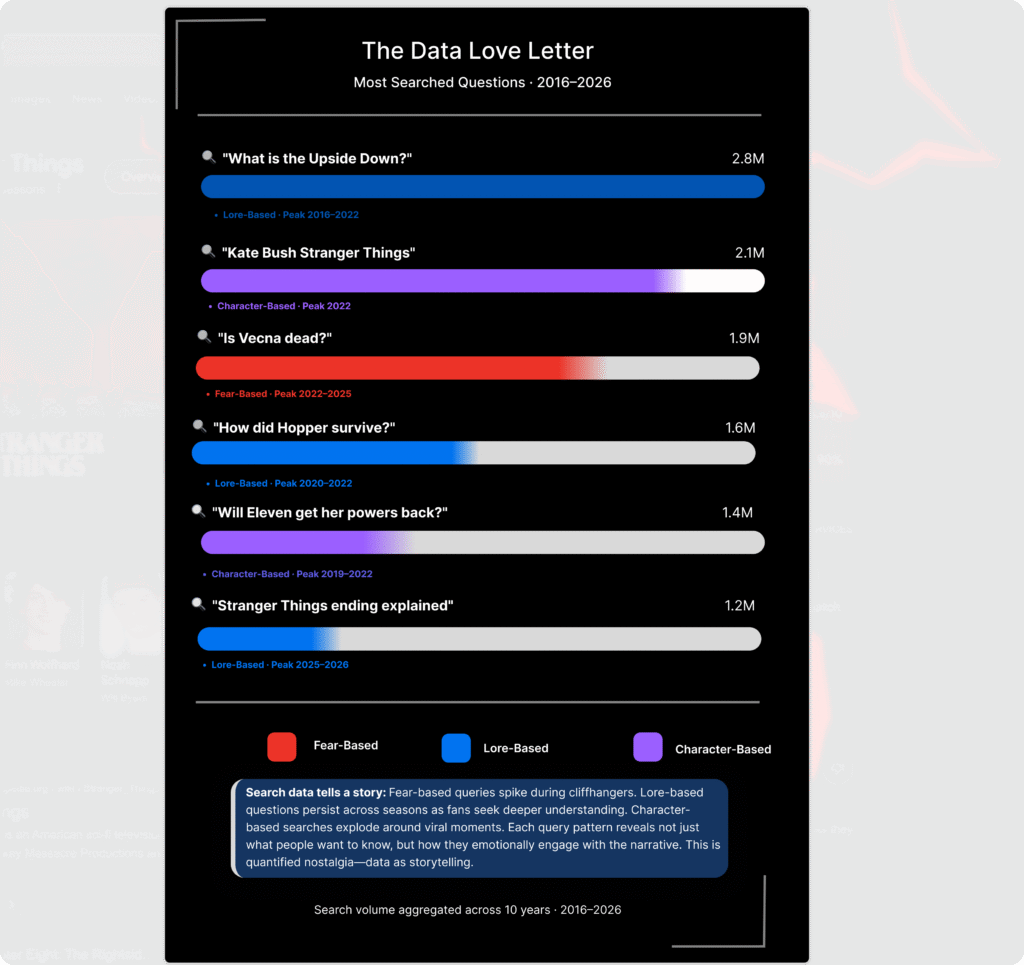

In many ways, this is a fascinating piece of content that taps into broader consumer technology trends. It opens with the promise that Google has “unlocked a decade of exclusive Search data”. The language is breathless, almost reverent. It frames search queries not as data points, but as artifacts of human curiosity.

The “Wrapped” Effect

We have seen this strategy before, most famously with Spotify Wrapped. The premise is simple: take user data (which is usually creepy), repackage it with nice graphics and nostalgic music, and suddenly it is a “love letter”.

Google’s video does exactly this. Specifically, it juxtaposes search trends with emotional clips from the show. It shows us that we searched for “Demogorgon costume” in 2016, “Never Ending Story lyrics” in 2019, and “Kate Bush” in 2022.

The brilliance here is that it makes the user the protagonist. This is brand storytelling at its most potent.

The show didn’t just happen on Netflix; it happened in the search bar.

We made it a phenomenon by asking questions about it.

This is “quantified nostalgia”. It validates the fandom by measuring it. It says, “Your obsession was real, and we have the charts to prove it.”

The Pivot to Behind-the-Scenes

Midway through the video, the tone shifts. We leave the data and move into behind-the-scenes (BTS) footage. We see the actors messing up lines, holding cameras, and laughing between takes.

At first glance, this seems disconnected from “Search trends”. Why is Google showing us bloopers?

The answer is that it humanises the machine. Google often feels like a black box—a cold, algorithmic monolith. By aligning itself with the warm, messy, human reality of the show’s production, Google borrows some of that warmth to create a more authentic brand story.

Furthermore, it reinforces the idea of “discovery”. The BTS footage represents the kind of deep-cut content you can find if you just… keep searching. It is a subtle promise: the show might be ending, but the rabbit hole goes forever.

Part III: The Scavenger Hunt and the “Gamification” of Querying

The most ambitious part of this campaign wasn’t in the videos at all, but in the activity they pointed towards: a digital scavenger hunt.

According to the launch details, users were invited to complete “20 quests” to unlock “four hidden rewards”. This involved solving riddles, finding specific images, and navigating through the “Upside Down” version of the search results.

This move is significant for any Google marketing analysis. It changes the fundamental interaction model of a search engine.

Traditionally, you search to leave. You type a query, you get a link, you click it, and you are gone. Google’s business model depends on you leaving (specifically, via an ad), but its user experience is designed for speed.

Conversely, a scavenger hunt does the opposite. It asks you to stay. It asks you to search for things you don’t actually need, just for the pleasure of finding them. It turns the search engine into a “walled garden” game.

Training the Algorithm (and the User)

Admittedly, there is a cynical read here. A scavenger hunt generates millions of high-intent queries. It looks great on a quarterly engagement report. It signals to advertisers that users are spending active time on the platform, not just passing through.

However, the more charitable (and perhaps more interesting) read is that it is training users in “query literacy”. By forcing people to search for specific terms to solve a puzzle, Google is subtly teaching them how to use the tool better. It is a tutorial disguised as a game.

It is a tutorial disguised as a game. It’s 80s nostalgia applied to internet usage itself.

For a generation that is increasingly used to just asking a chatbot to “explain this to me”, forcing them to hunt for specific keywords is almost a retro activity. It’s 80s nostalgia applied to internet usage itself.

Part IV: The Ethics of the “Love Letter”

We need to pause here and look at the “exclusive data” claim with a critical eye.

Although the phrase “we’ve unlocked a decade of data” sounds magical in a marketing video, in reality, it means “we have logged everything you have typed for ten years”.

Naturally, there is always a tension in these campaigns. Google is trying to be the friendly archivist of our culture.

But to be an archivist, you first have to be a surveillance system.

The video navigates this by keeping the data aggregated. It talks about “top searches” and “trending questions”, not individual histories. It stays on the right side of the “creepy line”.

However, marketers should be aware that this line is moving. As privacy concerns grow, the “look what we know about you” genre of marketing is becoming riskier. Spotify gets away with it because the data is personal and celebrates your taste. Google’s version is communal—it celebrates our collective curiosity.

This strategy works here because Stranger Things is a shared monoculture event. We are all in on the joke. But imagine this same technique applied to something more sensitive—health trends, political questions, or financial anxieties. It wouldn’t feel like a love letter; it would feel like a dossier.

Context is everything.

Part V: Why This Matters for Marketers (The “So What?”)

You are likely not marketing a global Netflix franchise or running the world’s biggest search engine. So, what is the utility here? What can you steal?

1. The “Platform as Stage” Strategy

First, stop thinking of your digital channels as static noticeboards. If you have a website, an app, or even a newsletter, how can you “dress” it for a campaign?

The “Upside Down” visual flip is expensive code, but the principle is cheap. For example, can you change your colour scheme for a launch? Alternatively, can you hide an Easter egg in your footer or tweak your UX microcopy?

Digital spaces are malleable. We often treat them like print—locked and rigid. They shouldn’t be. Surprise your users.

2. Data as Storytelling Material

Undoubtedly, you have data. You have sales figures, customer service queries, and most-read blog posts.

Rather than just putting them in a spreadsheet, narrativise them.

“Our most popular product was X” is a report.

“You guys were obsessed with X this winter” is a story.

Google’s “Bonus Search Trends” video proves that people love seeing a reflection of their own behaviour. It validates them.

Find the mirror in your data and hold it up to your customers.

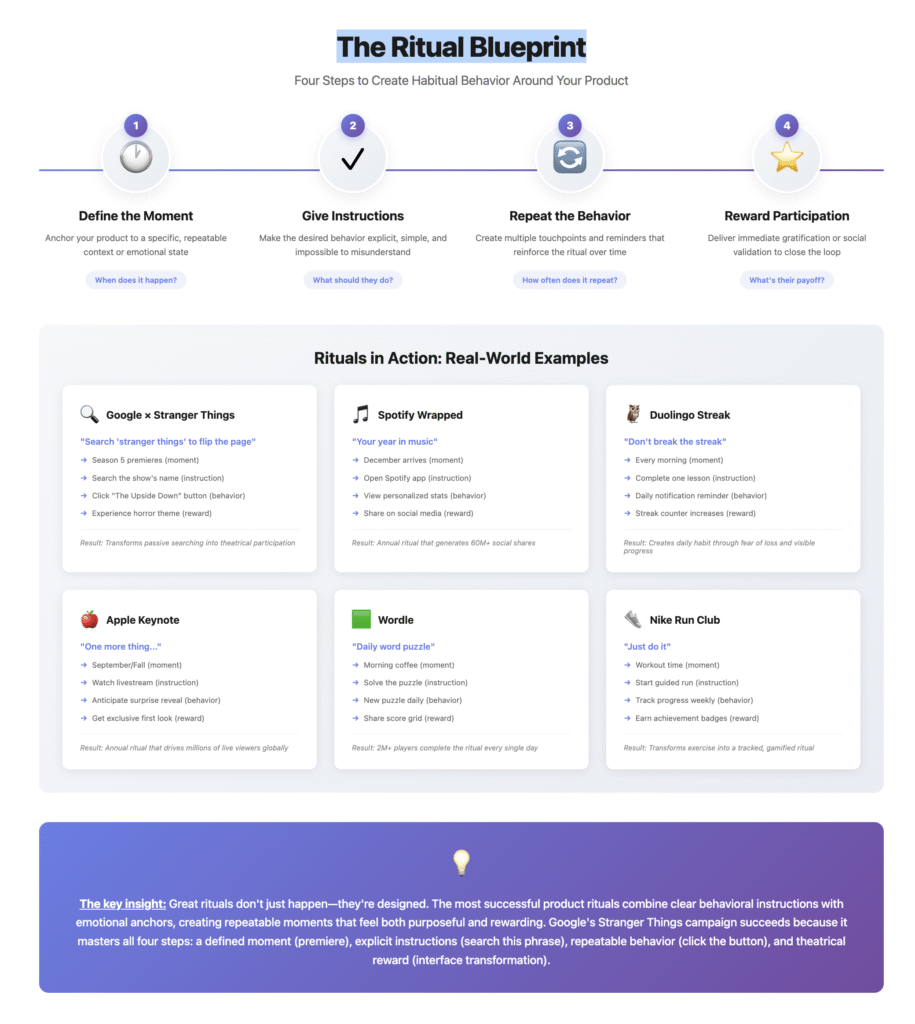

3. The Power of the “Ritual”

The “Watch Party” concept is a ritual. It gives people a specific way to consume the product. Unlike the more passive wellness campaigns we’ve seen from other streamers, this demands active participation.

Don’t just launch a product; give people a set of instructions on how to enjoy it. “Best served chilled.” “Read this with a coffee.” “Search this term before you watch.”

Rituals create belonging. If I search for the Easter egg, I am part of the club.

4. Nostalgia is a Trojan Horse

Frequently, we dismiss nostalgia as lazy. And it can be. Yet, when used correctly, it is a bridge.

Google used 80s nostalgia (the show) to sell a very modern capability (Lens, mobile search, AI).

If you are selling something new or complex, wrap it in something familiar. The Stranger Things aesthetic makes the tech feel less sterile.

Conclusion: The Last Search?

As Stranger Things finally wraps up its final season, there is a sense of an era ending. And perhaps, in a way, this is the end of an era for Search too.

The web is changing. The “ten blue links” model is under pressure from every side. We are moving toward a world of answers, agents, and feeds.

Ultimately, this campaign feels like a celebration of the “Classic Web”—the web where you had to hunt for things, where you typed keywords, where you fell down rabbit holes. It is Google saying, “Remember how fun this used to be?”

In short, it is a bold, expensive, and beautifully executed piece of defensive marketing.

It reminds us that while answers are efficient, questions are human.

And as long as we have questions, Google wants to be the one we ask—even if the answer is in the Upside Down.

Footnotes & Further Reading

- The Campaign Assets: You can watch the 31-second “Watch Party” spot here and the 8-minute “Search Trends” documentary here.

- The Easter Egg: For a technical breakdown of how the “Upside Down” effect works in the browser, Croma has a good summary of the Easter egg mechanics.

- The Scavenger Hunt: Details on the “20 quests” and the gamification element can be found in this report from Times of India.

- Netflix’s Numbers: For context on the scale of the show, Netflix’s own Tudum blog breaks down the viewership stats that drive these kinds of partnerships.

- Google’s Brand Studio: The collaboration was led by Google’s Brand Studio in partnership with Netflix, as detailed in MediaPost’s coverage.

On Google & Search

To understand the financial pressure driving this creativity, you should read Google’s Advertising Panic Reveals CPC Crisis. Furthermore, if the “theatrical” aspect of the Upside Down interested you, my analysis of The Manufactured Spectacle: Google’s 2025 Pixel Launch explores this trend of digital theatre in more depth. Alternatively, you can browse the full Google Marketing Analysis archive.

On UX & AI

The Stranger Things campaign relies heavily on interface design. For a broader look at how machines talk to us, check out Conversational AI & User Experience. In the same vein, the “watch party” prompts are a great example of UX & Microcopy: The Hidden Architecture. Finally, to see where this technology is heading next, look at Proactive AI Technology Trends.

On Brand Storytelling

Google isn’t the only streamer-adjacent brand trying to tell stories. In contrast to this campaign, see The Lazy Genius: Prime Video’s Wellness Miscalculation. If you are looking for the principles behind these moves, read my guide on Authentic Brand Storytelling. Similarly, for another example of a brand asking big questions, read Nike’s “Why Do It?”: An Analysis.