The $196bn sports sponsorship market has mastered buying visibility. It’s forgotten how to create value.

The sports sponsorship market will hit $196bn by 2032. Brands are spending more than ever. Yet 76% of marketing executives who invest in sports sponsorships can’t calculate ROI.

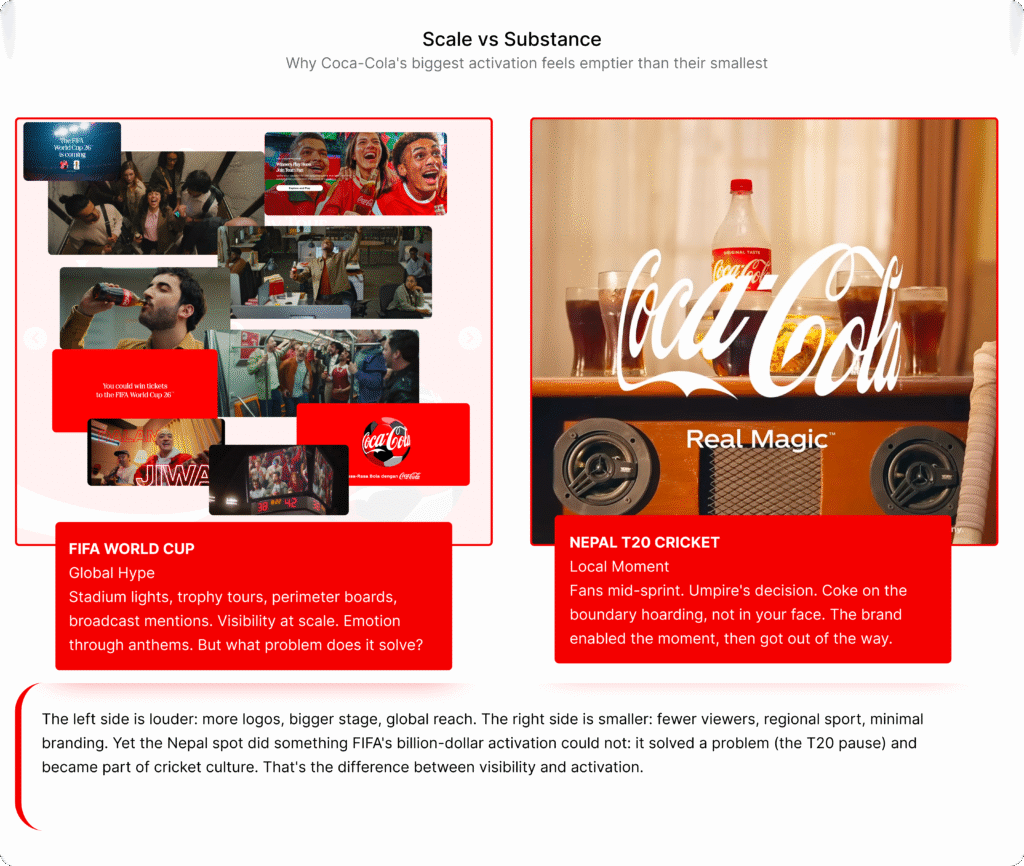

Coca-Cola’s FIFA World Cup 2026 campaign—featuring a Van Halen cover, sweepstakes mechanics, and four television spots with three different taglines—crystallises exactly why: the biggest sponsors have confused presence with activation, scale with strategy, and buying visibility with creating value.

Meanwhile, a 16‑second spot for Nepal’s T20 Cricket World Cup lands with far less fuss. There’s no contest. There’s no celebrity roster. Instead, you get one tense umpire review, crowd noise, and a brand that seems to know precisely why it’s there.

One works. The other reveals what’s broken in sports marketing right now.

Coca-Cola has mastered buying visibility. It still hasn’t worked out why it’s there once the logo is up.

The activation gap nobody’s naming

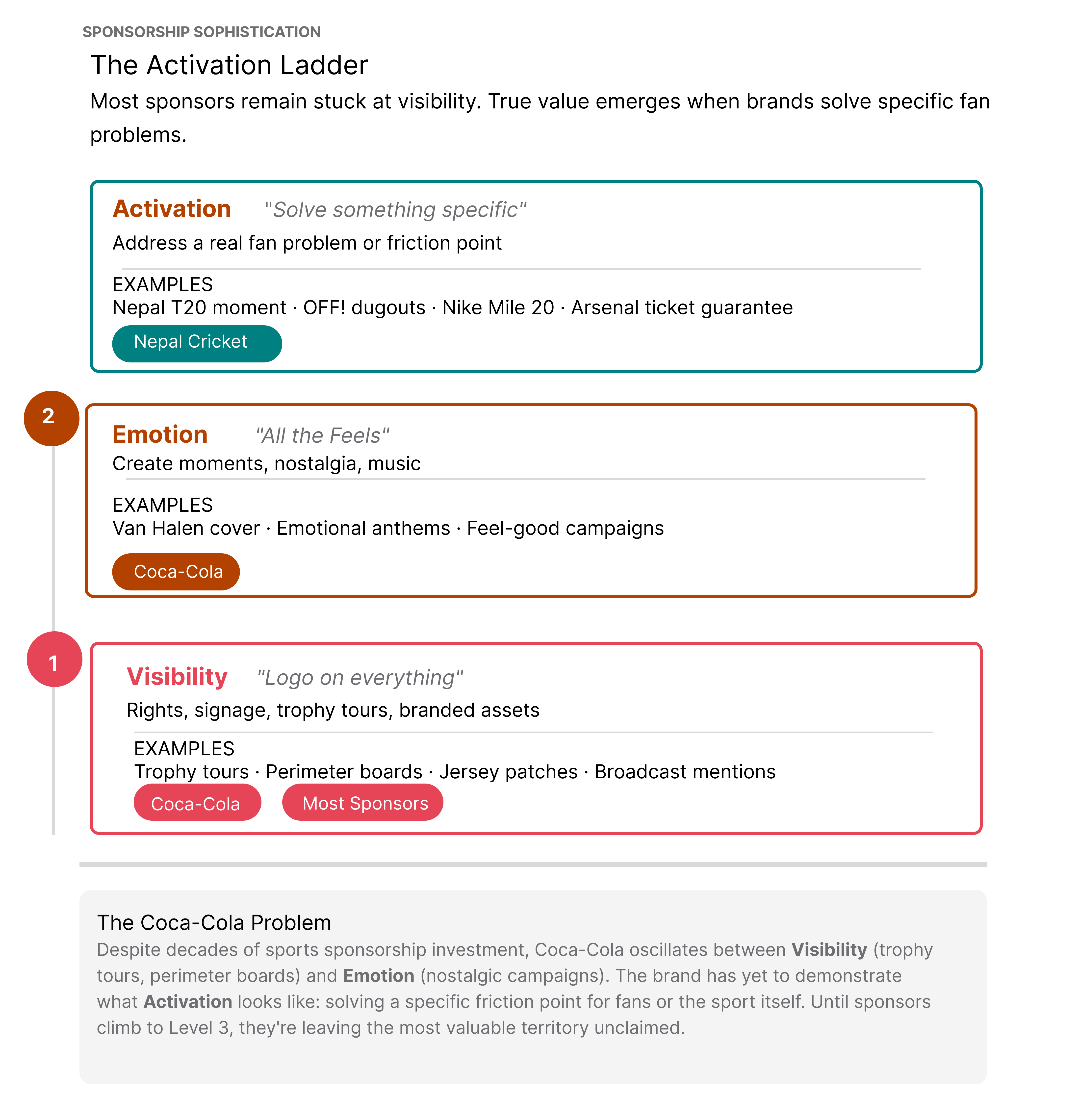

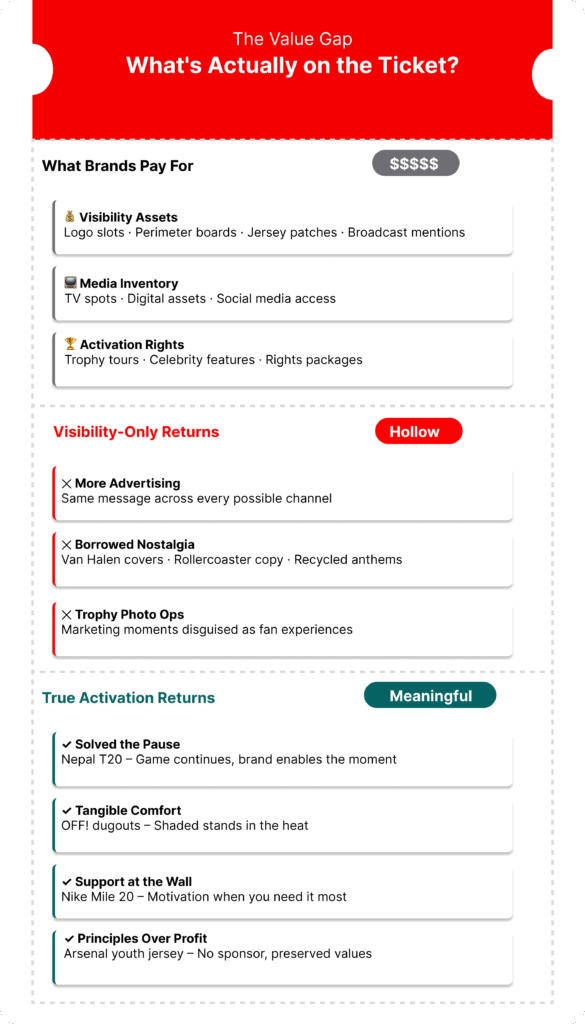

Sports sponsorship has entered what industry analysts call a period of “maturity over momentum”—growth continues, but with rising pressure for “operational credibility rather than surface-level storytelling”. In other words, brands have mastered buying rights (logo placement, naming deals, trophy tours) but failed at activation: using sponsorship assets to create genuine fan value and measurable business outcomes.

Coca-Cola’s FIFA campaign exemplifies what might be termed visibility theatre. For nearly 50 years, the brand has served as FIFA’s official soft drink sponsor across twelve tournaments. In 2026, it launched “All the Feels”—promising to “harness the incredible energy” of football and “transform emotions into real, tangible connections”.

However, watch the four spots (“Get the Feeling,” “Reveal the Feeling,” “Embrace the Feeling,” “Bubbling Up”) and a pattern emerges: the brand never establishes why it’s there. What problem does Coca-Cola solve for football fans? What experience does it enhance? Crucially, what need does it fulfil beyond claiming proximity to feelings that exist entirely independently of the beverage?

If you can’t answer “Why are we here?” your sponsorship isn’t a strategy. It’s just rent.

Four spots, zero clarity

“Get the Feeling” (15 seconds) leads with transactional mechanics: “Win thousands of prizes and a trip to see 3 FIFA World Cup matches”. This immediately contradicts any claim to authentic companionship. Rather than positioning itself as a fellow traveller, the brand becomes a lottery operator.

“Reveal the Feeling” and “Embrace the Feeling” (both 30 seconds) deploy match footage with exhortations to “drink in the excitement”. The messaging, however, is curiously passive—Coca-Cola doesn’t create feelings, doesn’t enhance experience, and doesn’t even claim refreshment. Instead, it simply instructs consumption whilst emotions occur independently.

“Bubbling Up”—the flagship spot featuring J Balvin, Amber Mark, Steve Vai, and Travis Barker covering Van Halen’s “Jump”—depicts fans “unable to contain their emotions” in public spaces as World Cup anticipation “spills into everyday life”. Here, at least, is an insight: football enthusiasm as contagious and uncontrollable. Yet Coca-Cola’s role remains undefined. Is it causing this effervescence? Is it channelling it? Or is it merely watching from the sidelines?

Three different taglines across four spots signals not creative abundance but strategic confusion—precisely the kind of messaging incoherence I’ve critiqued in campaigns like KitKat’s “Break the Loop”, where technical bravado can’t compensate for unclear brand purpose. Each spot grasps for a different emotional register because none has located a genuine insight connecting product to passion.

Recent sponsorship effectiveness research reveals that “the most successful sponsorships were not the loudest, but the best orchestrated”. Consequently, coherence across channels matters, and sponsorship tends to operate as a “fame-building brand channel” rather than a direct sales driver. But fame without activation yields impressions without conversion, awareness without loyalty, and presence without purpose.

The measurement mirage

Coca-Cola’s own history provides sobering precedent. In 2014, the “World’s Cup” campaign generated over 2 billion impressions and achieved top‑10 chart positions in more than 40 countries. Despite this apparent success, the campaign “failed to lift Coca-Cola profits”, with revenue declining 1% year‑on‑year in Q2 2014.

For 2026, the declared metrics remain notably vague: “transforming emotions into real, tangible connections” and “bringing fans closer than ever before”. But “connections” and “closeness” resist quantification. Therefore, the key questions persist: what constitutes a connection, and when does emotional engagement convert to commercial value?

The Trophy Tour—visiting 75 cities across 30 countries—has engaged “over 4 million fans in 182 markets” across its 20‑year history. Nevertheless, 4 million participants over two decades, distributed globally, represents fractional penetration of Coca-Cola’s consumer base. Moreover, participation (queuing to photograph a trophy) provides no insight into purchase behaviour, brand preference, or long-term loyalty.

This exemplifies the broader measurement crisis: 40% of sponsors spend less than 1% of budgets on measurement, whilst three‑quarters struggle to calculate ROI. The challenge stems from sponsorship’s diffuse impact across awareness, perception, and sales—outcomes that resist simple attribution.

In practice, when brands can’t articulate what they’re measuring, it’s often because they haven’t defined what they’re actually trying to do.

Impressions without activation are just very expensive views.

What earned activation looks like

Effective sponsorship activation solves a specific problem for fans or participants that aligns with brand capabilities. Not abstract problems like “need more feelings”. Instead, think concrete problems with tangible solutions.

OFF!® and Little League

The insect repellent brand didn’t just slap logos on youth baseball fields. Instead, it installed repellent stations near dugouts, distributed free protection kits to families, and shared safety information through league newsletters. Consequently, the activation addressed a clear, everyday problem—mosquitoes and ticks during games—that every parent and player recognised. OFF!® earned attention by improving the experience, not just occupying it.

Nike at Mile 20, Chicago Marathon

By mile 20, runners hit the wall—the toughest mental stretch. Rather than generic brand messaging, Nike planted a high‑energy motivation zone precisely there, with raised platforms, DJs, and volunteers in Nike Run Club gear leading nonstop chants. As a result, the activation met runners when they needed it most, transforming a stretch of fatigue into a surge of emotion. Nike turned its brand promise into lived experience at the exact moment it mattered.

Arsenal and Adidas

For youth academy teams, the brands created jerseys with no sponsor logo—prioritising player safety and development over commercial visibility. In doing so, the activation replaced messaging with conviction. Fans respected the restraint; the community recognised genuine investment. Ultimately, Arsenal and adidas earned credibility by aligning visibility with authentic impact.

The pattern is simple: each activation answers “Why are we here?” with a verb other than “support,” “celebrate,” or “bring together”. Specifically, OFF!® protects. Nike motivates. Adidas develops. Coca-Cola’s FIFA campaign? The verb never appears.

The best sponsors don’t shout the loudest. They solve the clearest problem.

The Nepal counterpoint

Then there’s Coca-Cola’s 15‑second spot for Nepal’s T20 Cricket World Cup debut. In contrast to the FIFA work, it operates entirely differently.

Live-style commentary—“We are going to check. I think this could be the moment”—drops viewers into high-stakes DRS tension without showing replay or decision. Meanwhile, crowd noise and sprinting players signal collective jeopardy. Copy outside the film explicitly frames this as “more than cricket”—“national pride, unity, and believing in our team… one team, one dream, one nation.”

Crucially, the brand shows restraint: no contest mechanic, no QR code, no hard sell. Just a Coke‑plus‑crest identity inside a local story about Nepal arriving on a global stage.

This is the kind of people-powered marketing authenticity I explored in Swiggy Wiggy 3.0’s campaign—where brands earn attention by elevating participants rather than overshadowing them.

Comparing the two approaches

| Dimension | FIFA “All the Feels” | Nepal T20 |

|---|---|---|

| Activation strategy | Visibility + borrowed nostalgia | Moment ownership |

| Fan problem solved | None articulated | Giving voice to national pride |

| Brand role | Undefined “companion” | Partisan supporter |

| Cultural specificity | Global, de-contextualised | Local, underdog narrative |

| Transactional overlay | Heavy contest/prize mechanics | None—trust that pride works |

| Measurement potential | Impressions, reach, Trophy Tour attendance | Sentiment lift, community ownership in target market |

Nepal demonstrates earned activation: the brand attaches to a specific, culturally legible moment (DRS‑style tension, small nation on a big stage), and Coca-Cola’s presence feels natural rather than imposed. Furthermore, the work grounds itself in a concrete situation—something every cricket watcher recognises viscerally—rather than abstract claims about “feeling it all”.

It also aligns with Coca-Cola’s wider ICC strategy in South Asia: backing underdog teams and regional tournaments to feel locally embedded rather than globally imposed. Indeed, the brand has explicitly framed its cricket partnerships as contextual, real‑time engagement rather than scale theatre.

The purpose-washing problem

When activation fails, brands often retreat to “purpose” claims ungrounded in operational reality. Coca-Cola’s FIFA rhetoric exemplifies this: “transforming emotions into real, tangible connections,” “bringing communities together,” positioning itself as “essential companion through highs and lows”.

However, this language reveals a troubling substitution: the brand is monetising community that exists independent of the product, then claiming credit for facilitating it. Football fandom creates community. Coca-Cola simply places itself adjacent whilst invoking connection. This echoes the timing missteps I analysed in Swiggy’s Durga Puja dog campaign—where noble intentions met tone‑deaf execution because the brand prioritised campaign calendar over contextual awareness.

What purpose-washing looks like

This exemplifies what scholars call “purpose-washing”—when purpose appears only in marketing and communications rather than as authentic operational philosophy. Notably, research identifies two forms:

- Tail wagging dog: Purpose as advertising tactic rather than management philosophy. Consequently, campaign activity isn’t backed by real business commitment. Investment goes toward slick production and media buys, not delivering social impact.

- Corporate scale makes inconsistency inevitable: Sweeping purpose claims (like “bringing communities together”) that massive companies can’t operationally deliver. Inevitably, the gap between rhetoric and reality becomes untenable.

For Coca-Cola, there’s no operational connection between soft drink production and “bringing communities together”. Rather, the sponsorship investment secures commercial access, not cultural contribution. The Trophy Tour, Panini partnership, and contest mechanics represent scale theatre—visibility deployed to justify the claim—not substantive activation.

Moreover, the brand faces structural contradictions: health concerns around sugar content sit uneasily with “essential companion” framing. This doesn’t mean Coca-Cola can’t sponsor sports—but it does mean vague purpose claims without activation strategy ring hollow.

The backlash cycle is accelerating. Research shows that Gen Z “can spot manufactured authenticity instantly” and gravitates towards “raw, spontaneous content” over “overscripted videos”. Consequently, when brands deploy sophisticated affective triggers—nostalgia, belonging, collective euphoria—to sell products with marginal functional relevance, audiences increasingly recognise the manipulation.

Purpose without practice is just a nicer word for positioning.

The nostalgia problem

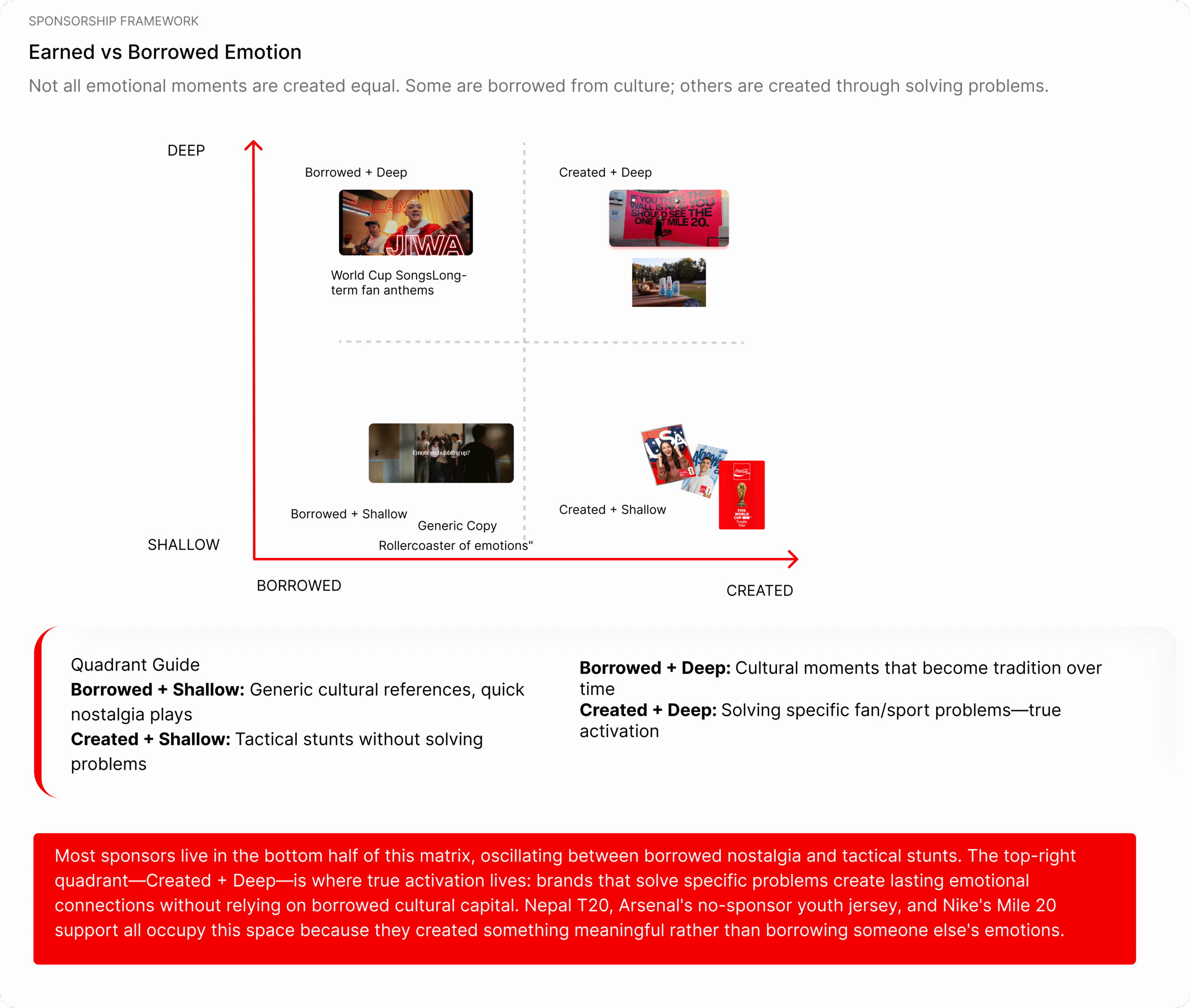

Which brings us to the Van Halen cover. Studies on nostalgia marketing effectiveness reveal that “consumers are more receptive to nostalgic advertising when the brand’s retro messaging aligns with its historical brand identity”. Thus, a nostalgic ad from Nike or Coca-Cola should feel more genuine than a start‑up adopting random vintage styles because the brand actually has heritage.

Yet “Jump” isn’t Coca-Cola heritage—it’s borrowed capital. The 1983 Van Halen hit carries associations with triumph and celebration; its number‑one status guarantees cross‑generational recognition. Meanwhile, the multi‑artist collaboration (J Balvin for Latin American youth, Travis Barker for Gen X punk nostalgia, Steve Vai for guitar credibility) signals calculated demographic targeting.

This is cultural appropriation masquerading as cultural contribution—a theme I’ve explored when analysing how brands hijack trending cultural moments without genuine innovation.

In essence, Coca-Cola hasn’t created a cultural artefact for this World Cup; it has licensed and remixed existing emotional associations. The artist assembly feels focus‑grouped rather than felt—a Spotify algorithm rendered as creative strategy.

Research on “vicarious nostalgia” shows Gen Z engaging with “a past they never lived” through media‑mediated representations. As a result, this makes them uniquely susceptible to retro‑themed advertising—but also uniquely attuned to “aesthetic exploitation,” when nostalgia feels forced or opportunistic. For a campaign ostensibly celebrating “raw emotions” and “shared passion,” the clinical assembly of musical signifiers reads as profoundly inauthentic.

Three lessons for marketers

1. Answer “Why are we here?” before buying rights

Before purchasing sponsorship, define the specific fan or participant problem you’re solving. If the answer is “visibility” or “association,” you haven’t done the strategic work.

Test: can you articulate your brand role in one sentence with a verb other than “support,” “celebrate,” or “bring together”?

- “We celebrate football passion”

- “We provide refreshment during tense matches”

- “We fund grassroots access for communities priced out”

- “We document underdog stories that wouldn’t otherwise get told”

2. Cultural contribution beats cultural appropriation

Sponsorship effectiveness depends on perceived authenticity. Consequently, borrowing existing cultural capital (Van Halen covers, trophy tours, celebrity rosters) without creating new cultural artefacts signals opportunism.

Earned activation looks like: Arsenal taking a commercial hit for safety conviction. Nepal giving language to a specific national moment. Nike owning the hardest mile because it aligns with brand identity.

In contrast, borrowed activation looks like: remixing 40‑year‑old hits with focus‑grouped artists. Abstract claims about “bubbling up” that could apply to any sport. Scale as substitute for strategy.

3. Measure activation, not just awareness

Shift metrics from impressions, reach, and hashtag volume to:

- Specific problem solved for a specific fan segment

- Behaviour change enabled (hydration, safety, access)

- Community ownership of the brand moment

- Purchase intent among activated segment versus a control

- Long‑term sentiment shift in the target market

Ultimately, Nepal may generate fewer global impressions than the FIFA work, but it likely delivers higher sentiment lift and purchase intent in the Nepal market than the global campaign delivers anywhere.

The next wave of sponsorship winners won’t be the brands with the biggest logos. They’ll be the ones fans would miss if they left.

Coda

Sports sponsorship has hit $70bn annually by doing one thing well: buying visibility. However, the next tranche of growth will belong to brands that do the harder thing—activating that visibility into genuine fan value.

Coca-Cola’s FIFA World Cup 2026 campaign is expensive proof that 50 years of sponsorship investment doesn’t automatically teach you what you’re there to do. Half a century of logo placement, trophy tours, and vague invocations of “connection” have produced scale without strategy, presence without purpose.

The Nepal spot—modest, specific, grounded—suggests the alternative. It demonstrates that brands solving real problems for real fans in real moments will always beat brands that simply occupy space whilst claiming to embody all feelings.

So here’s the uncomfortable question that precedes effective activation: if you weren’t paying to be there, would anyone actually want you there? And, more importantly, why?

Coca-Cola spent 50 years avoiding that question. Its 2026 campaign—with borrowed nostalgia, transactional overlays, and strategic hollowness—suggests it still doesn’t have an answer. The market won’t wait much longer for one.

Related reading:

- Brand Anthem in the Age of Algorithms: Swiggy Wiggy 3.0 Campaign

- Break the Loop, Mind the Bump: A Wry Audit of KitKat’s Latest Musical Break

- Swiggy’s Puja Dog Campaign Was a Bold Move—But Missed Its Mark

- The September Siege: When Smartphone Brands Lost Their Collective Sanity

Footnotes

- Sports sponsorship maturity / “maturity over momentum”

Body: linked on “$196bn by 2032” and “maturity over momentum” →

Footnote:Rosemary Sarginson – Sports Sponsorship 2026: Maturity Over Momentum

https://www.linkedin.com/posts/rosemary-sarginson-547a2817_sports-sponsorship-in-2026-ten-trends-set-activity-741652319898639564-E6R5 - 76% of CMOs can’t measure ROI

Body: linked on “76%… can’t calculate ROI” →

Footnote: Sports Business Journal article (Forrester survey)https://www.sportsbusinessjournal.com/Articles/2025/11/03/investment-in-sports-sponsorships-is-rising-yet-cmos-struggle-to-calculate-return-on-investment - Coca‑Cola’s official campaign release

Body: linked on “nearly 50 years” and “transforming emotions…” →

Footnote:https://www.coca-colacompany.com/media-center/coca-cola-puts-fan-emotions-first-in-fifa-world-cup-2026-campaign.html - Adweek creative write‑up

Body: linked on “harness the incredible energy” and “essential companion” →

Footnote:https://www.adweek.com/creativity/coca-cola-captures-all-the-feels-of-soccer-fans-for-world-cup-2026/ - Billboard on the Van Halen “Jump” cover

Body: linked on “covering Van Halen’s ‘Jump’” and “1983 hit” →

Footnote:https://www.billboard.com/music/rock/van-halens-jump-all-star-update-fifa-world-cup-campaign-1236164849/ - Marketing Dive on the campaign and “bubbling up”

Body: linked on “spills into everyday life” →

Footnote:https://www.marketingdive.com/news/cokes-world-cup-campaign-taps-into-unifying-power-of-fan-emotions/810580/ - WARC on sponsorship orchestration / fame vs. loudness

Body: linked on “most successful sponsorships… best orchestrated” →

Footnote:https://www.warc.com/newsandopinion/opinion/big-brand-opportunities-in-2026-sports/7255 - Marketing Week on 2014 “World’s Cup” failing to lift profits

Body: linked on “2 billion impressions” and “failed to lift profits” →

Footnote:https://www.marketingweek.com/share-a-coke-and-world-cup-marketing-fail-to-lift-coca-cola-profits/ - Stadium Nest on the 2026 Trophy Tour numbers

Body: linked on “over 4 million fans in 182 markets” →

Footnote:https://stadiumnest.com/2025/12/16/world-cup-hype-fifa-coca-cola-launch-biggest-ever-trophy-tour-for-2026-2107 - Bottom Line Analytics on sponsorship ROI measurement

Body: linked on “40% of sponsors spend less than 1% on measurement” →

Footnote:https://bottomlineanalytics.com/the-elusive-measurement-dilemma-of-sports-sponsorship-roi/ - MVP Visuals examples (OFF!, Nike, Arsenal/adidas)

Body: linked three times in the activation section →

Footnote:https://mvpvisuals.com/blogs/resources/sports-sponsorship-activation-examples - Coca‑Cola ICC cricket commitment (South Asia context)

Body: linked on “wider ICC strategy” →

Footnote:https://www.coca-colacompany.com/media-center/heres-how-coca-cola-is-committed-to-icc-world-cup-and-cricket - Purpose‑washing definition / context

Body: linked on “scholars call purpose‑washing” →

Footnote:https://www.cmoalliance.com/the-problem-with-purposewashing-for-cmos-and-brands/ - Branding Trends 2026 / Gen Z spotting “manufactured authenticity”

Body: linked on “research shows… Gen Z can spot manufactured authenticity instantly” →

Footnote:https://digital-business-lab.com/2026/01/branding-trends-rise-authenticity-purpose-driven-strategies/ - ACR Journal – Digital nostalgia and Gen Z

Body: linked on “studies on nostalgia marketing effectiveness” and “vicarious nostalgia” →

Footnote:https://acr-journal.com/article/digital-nostalgia-marketing-how-past-centric-ads-affect-gen-z-consumption-1527/