On New Year’s Eve, Apple released a 65-second advertisement that epitomises everything going awry in contemporary marketing. Two detectives stand in a shadowy warehouse. One lectures his bemused partner about the “crash zoom” – how it “heightens tension,” “builds suspense,” and “foreshadows danger” – whilst the camera obligingly zooms dramatically on mundane objects: a dripping pipe, a scuttling rat, a deflating balloon.

The ad is arch, knowing, deliberately theatrical. And it’s precisely the sort of clever advertising that risks making ordinary people feel uninformed and alienated.

Why this matters now

Apple’s “Detectives 8x Zoom” ad arrives at a peculiar inflection point for marketing. The advertising landscape is fundamentally shifting as we enter 2026. Trust has become currency as third-party cookies vanish, whilst authenticity and community now serve as competitive advantages.

In this environment, where consumers demand transparency and expect brands to respect their intelligence, Apple chose to make an in-joke about cinematographic technique.

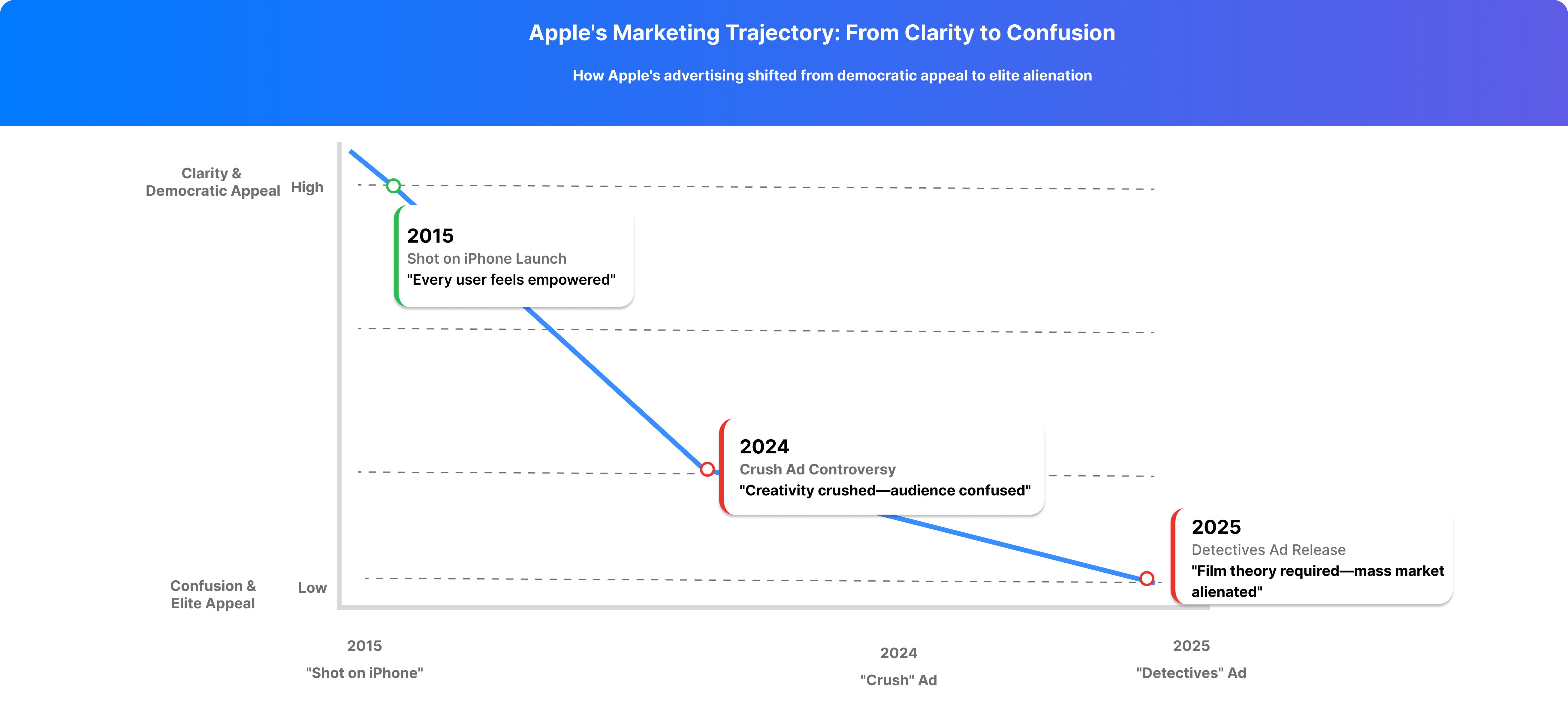

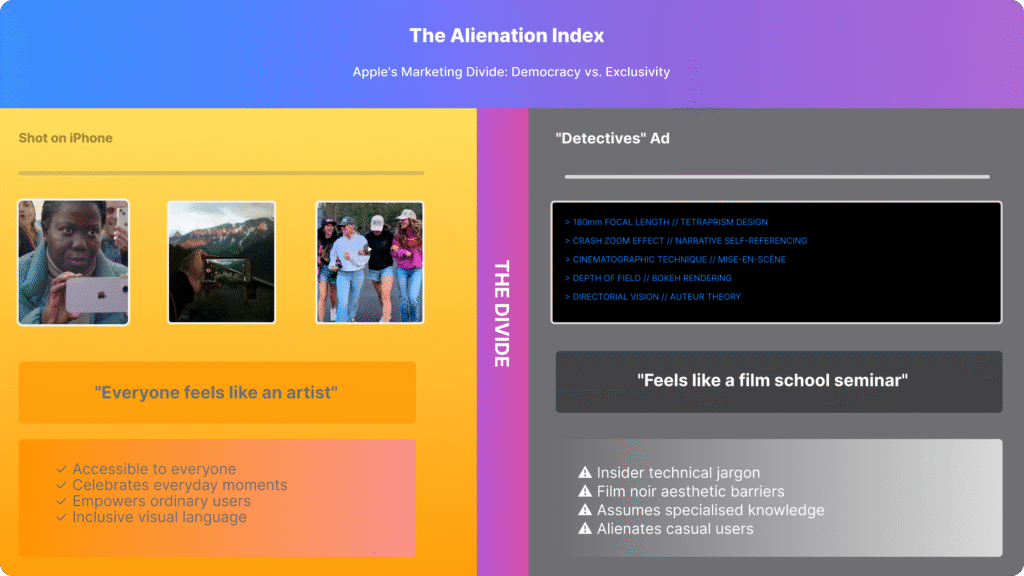

The ad forms part of the “Shot on iPhone” campaign – one of modern marketing’s most successful platforms, generating $14 billion in incremental iPhone sales and 29 million Instagram posts since 2015. Yet Apple abandoned the democratic authenticity that built this franchise for something altogether more exclusionary: a meta-commentary that assumes viewers understand what a crash zoom is and appreciate the irony of using the technique whilst simultaneously explaining it.

This isn’t universal language. It’s film school semiotics.

If you’ve already read your earlier piece on Apple’s iPhone 17 Pro marketing, you’ll recognise the pattern: strong product, confident media spend, and then a creative leap that doesn’t always land where ordinary users actually live.

The self-referential gambit: When insider appeal backfires

Self-referential advertising – ads that acknowledge their own status as advertisements – can work remarkably well when executed with precision. Academic research in Innovative Marketing shows significant positive correlations between such ads and both brand perception (r = 0.777) and brand attitude (r = 0.712), particularly amongst Gen Z and Millennial audiences.

When audiences recognise that a brand is “in on the joke,” authentic connections emerge through transparency and wit. But here’s the critical finding: self-referential content succeeds by “appealing to consumers’ authentic self,” not by testing their cultural literacy.

The literacy trap

Research on self-referencing effects from the Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services reveals a crucial distinction. Analytical self-referencing – where viewers connect content to their own direct experience – generates statistically significant increases in behaviour intention (p = 0.022).

Narrative self-referencing shows weaker effects by contrast. When the narrative requires cultural knowledge to decode, purchase intent suffers, particularly for consumers making pragmatic buying decisions.

Self-referential content succeeds by “appealing to consumers’ authentic self,” not by testing their cultural literacy.

The “Detectives” ad demands specific cultural knowledge: understanding what a crash zoom is, recognising how it functions as deliberate stylistic choice, and grasping why the meta-joke is meant to land. Film enthusiasts will appreciate it. Yet the pragmatic majority considering their next smartphone? They’ll simply feel excluded.

Humour’s hidden limitations

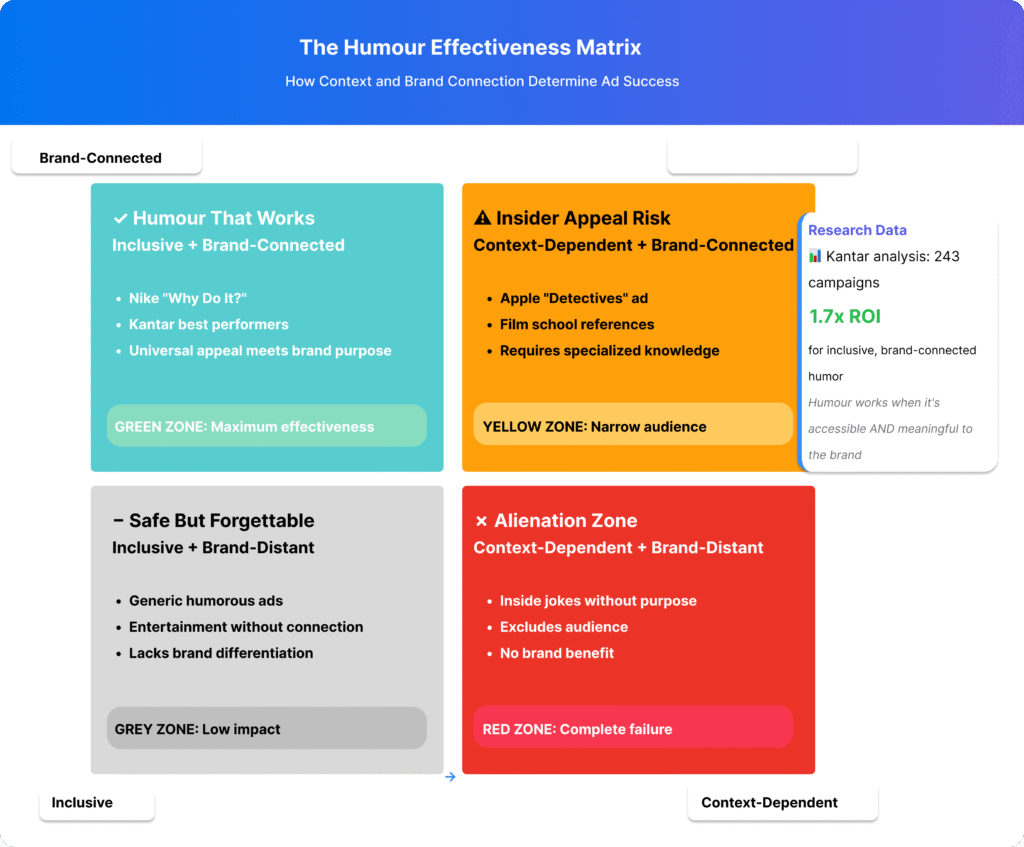

Research on humour in advertising reveals a nuanced picture that complicates the “Detectives” ad’s strategy. Kantar’s 20-year analysis of global advertising data shows that whilst humour correlates with improved brand attitudes and purchase intent, not all humour works equally well.

A critical finding emerges: humour only works when it connects to the brand.

When context defeats the joke

Meta-analysis of humour research in Marketing Week confirms that humorous ads show statistically significant benefits (p < 0.001) across six variables: attitudes towards the ad, attitudes towards the brand, attention, positive emotions, reduction in negative emotions, and purchase intent.

Yet there’s a crucial caveat: context-dependent humour is categorically different from inclusive humour. Specifically, Kantar’s creative effectiveness research notes that inside jokes, whilst entertaining to initiates, risk “lost in translation” effects.

The “Detectives” ad borrows film noir conventions and references cinematographic technique. It assumes cultural capital that a substantial portion of Apple’s mass-market iPhone audience won’t possess. For viewers already film-literate, the ad entertains. For everyone else, it alienates.

If that sounds familiar, your essay on September smartphone marketing 2025 diagnosed something similar: brands talking to each other and to award juries, rather than to the people actually buying the devices.

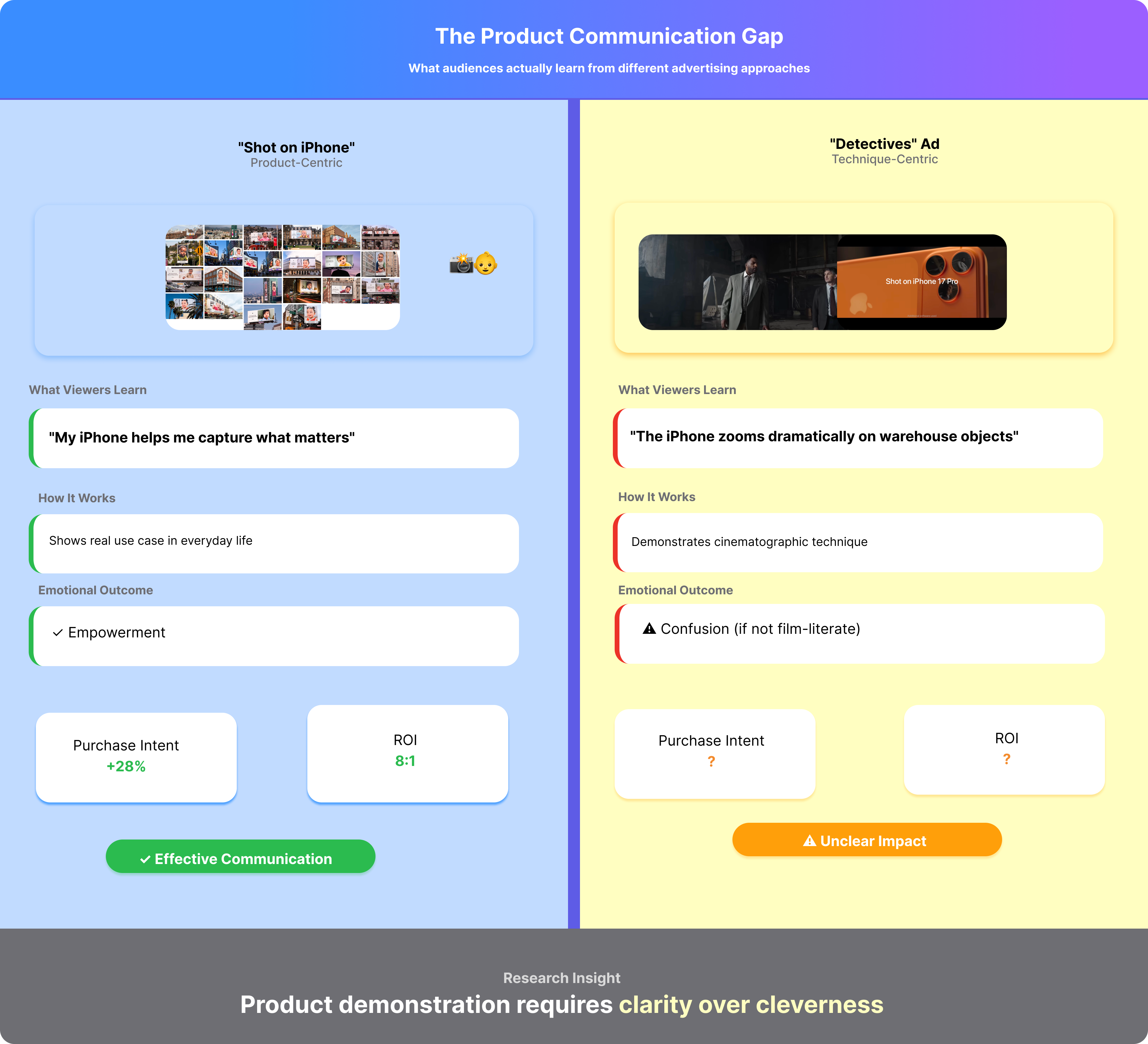

The product demonstration problem

Perhaps most damningly, the ad fails the fundamental test of product communication. The iPhone 17 Pro’s 8x optical zoom represents genuine engineering achievement: a 200mm equivalent focal length using a tetraprism design with a 48MP sensor that’s 56% larger than its predecessor.

Consider what the market signals: camera quality evolved from an 11% purchase driver in 2014 to 42% by 2019. Smartphone photography enthusiasts – approximately 15% of iPhone Pro purchases – care about sensor size, focal length, and low-light performance.

What the ad actually shows

Unfortunately, the “Detectives” ad addresses neither technical enthusiasts nor mass consumers. Specifications are absent. Notably, relatable use cases are missing. Instead, it demonstrates that the iPhone can execute a cinematographic technique most people have never heard of, in service of a genre parody most viewers won’t recognise.

The original campaign’s success

The original “Shot on iPhone” campaign achieved perfect product-audience alignment: every image was the product demonstration. Consequently, users who engaged with this content were 28% more likely to consider iPhone in their next purchase.

Furthermore, the campaign delivered an 8:1 return on advertising spend versus an industry average of 2.5:1. This demonstrates the power of showing product benefit through authentic use, not through technical display.

Our broader critique of iPhone 17 Pro marketing sits neatly beside this. There, the question was whether the “Awe Dropping” narrative justified itself. Here, the question is whether Apple remembers why “Shot on iPhone” worked so well in the first place.

Why the technique fails here

The “Detectives” ad uses the 8x zoom merely as narrative device. It demonstrates crash zooms – a technique often created in post-production through digital manipulation rather than optical zoom during capture.

Viewers learn that the iPhone zooms dramatically on warehouse objects. Ultimately, they don’t learn what this might mean for their own photography.

A pattern of brand misalignment

This isn’t an isolated misstep. Indeed, Apple pulled four problematic marketing videos since May 2024. The infamous “Crush” iPad Pro ad showed creative tools being literally crushed by an industrial press. As a result, the creative community Apple claims to champion reacted with horror.

Failed promises and credibility loss

Similarly, Apple Intelligence features were marketed before being delivered. Consumers felt disappointed and misled by promises the company later abandoned. This pattern of over-promising erodes trust and undermines even well-intentioned creative work.

What critics are saying

The consistent criticism emerges: cleverness that congratulates itself rather than empowering users.

As one advertising analyst observed about recent Apple campaigns: “Going too astray of the brand’s original message; making it about the consumer… it’s what the user does with the product, not that the product can replace everything.”

The “Detectives” ad displays the same symptoms. Advertising about advertising. Technique referencing technique. Self-awareness about self-awareness. Commercial benefits aren’t eroded by the cleverness; they’re obscured by it.

If you place this beside our critique of Apple’s “No Frame Missed” accessibility campaign, a pattern emerges: when Apple centres real people and concrete use, the work sings; when it centres itself, the work frays.

The ads business expansion

Meanwhile, Apple aggressively expands its own advertising business. The company rebranded “Apple Search Ads” to simply “Apple Ads” and prepares to flood the App Store with sponsored placements throughout 2026.

The irony is stark: the company that once positioned itself as the anti-advertising technology champion is becoming an advertising company. Simultaneously, it produces advertising for its own products that prioritises Apple’s cleverness over customer needs.

This sits neatly alongside our analysis of Google’s advertising panic and CPC crisis: platforms inch deeper into monetisation, while their own brand stories start to wobble under the weight of those incentives.

What research actually tells us

Academic research on advertising effectiveness from Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking demonstrates that self-referencing effectiveness depends critically on audience connection. Analytical self-referencing – where viewers connect content to their own direct experience – generates statistically significant increases in behaviour intention (p = 0.022).

By contrast, narrative self-referencing shows weaker effects, particularly when the narrative requires cultural knowledge.

The personal relevance factor

Interestingly, research on personal relevance from UCL’s Department of Psychology reveals a counterintuitive finding: people prefer personally relevant advertising and remember it better. However, personal relevance doesn’t consistently enhance purchase intent in expected ways.

Overly clever self-reference may trigger critical scrutiny – precisely what you want to avoid when selling premium products. As a result, consumers become suspicious of messaging that seems designed more to showcase advertising skill than to serve their needs.

The humour effectiveness ceiling

Most critically, foundational research on humour shows that humour effectiveness depends on brand connection. According to Kantar’s analysis of 243 campaigns from 2012 to 2020, humorous campaigns had 1.7 times more “very large business effects” (such as higher profits or market share) compared to 1.4 for non-humorous campaigns.

But this assumes the humour lands – that it connects to the brand promise rather than distancing from it.

The “Detectives” ad’s humour doesn’t serve the product. Ultimately, it serves the advertising itself.

The democratic versus elite divide

Apple’s most successful advertising excelled at accessibility. The original iPhone ads showed a finger navigating an intuitive interface. The “Shot on iPhone” campaign required no technical literacy whatsoever; ordinary people simply looked at beautiful photographs.

This democratic approach reflected Steve Jobs’s founding philosophy: technology should be accessible, intuitive, and human. Consequently, Apple became cool not through cleverness, but through genuine innovation in making powerful technology feel approachable.

How the new ad breaks the formula

The “Detectives” ad betrays this philosophy entirely. Barriers to entry are erected. Cultural capital becomes prerequisite. Viewers must possess knowledge that substantial portions of Apple’s mass-market audience simply won’t have.

Cultural capital becomes prerequisite.

Here’s the fundamental problem: the iPhone 17 Pro, whilst positioned as a “Pro” device, competes in a market where ordinary consumers make decisions based on whether a camera helps them capture life better. The ad treats viewers as either inside an in-group (those who understand the meta-commentary) or outside it.

Our work on Amazon’s celebrity marketing strategy explores a similar tension: global brands trying to be clever and premium, but still needing to feel legible and human in very different cultural markets.

The niche versus mass challenge

Research on niche versus mass marketing consistently demonstrates that this strategy sacrifices reach for the illusion of prestige. The “Detectives” ad succeeds only if your audience is already film-literate. For everyone else, you’ve created content that alienates rather than invites.

In our September smartphone siege piece, the same theme appeared in a different costume: brands chasing each other and Apple for attention, while the user quietly exits the chat.

Where this leaves Apple

As marketers navigate 2026, authenticity serves as competitive advantage. Crucially, consumers demand transparency and respect for their intelligence. Yet Apple produced advertising that seems more interested in impressing advertising professionals than serving actual users.

The iPhone 17 Pro’s 8x zoom deserved better than a knowing wink. It deserved to be shown making ordinary people’s lives more extraordinary.

Ultimately, that’s what Apple does best when it remembers to put the user at the centre of the story, not the advertising technique.

The contrast in outcomes

The original “Shot on iPhone” campaign worked because it made every user feel like an artist. The “Detectives” ad makes every viewer feel tested on film theory knowledge.

One approach is democratic and empowering. The other is exclusionary and self-congratulatory.

If you place this next to our breakdown of Nike’s “Why Do It?” campaign, the contrast is instructive: Nike extends the circle, inviting more people into its “why”; Apple, in this case, seems to tighten the circle around people who already speak the language of craft.

For a company whose founding philosophy was to make technology accessible, intuitive, and human, this represents not just a creative misstep but a betrayal of brand purpose. The research is clear: humour works only when connected to brand promise, self-referencing succeeds through authentic self-connection rather than cultural gatekeeping, and product demonstration requires clarity over cleverness.

The final reckoning

In conclusion, the “Detectives” ad reads as a misunderstanding of Apple’s own marketing principles.

The crash zoom, it turns out, isn’t just a cinematographic technique. It’s become a metaphor for Apple’s current advertising trajectory: moving quickly from clarity to confusion, from democratic to elite, from user empowerment to insider self-reference.

And unlike the technique demonstrated in the ad, this zoom isn’t capturing anything worth celebrating.

Sources

How Apple’s “Shot on iPhone” Campaign Turned Customers Into Creators — LinkedIn

Apple Shares ‘Detectives’ Ad Promoting iPhone 17 Pro — MacRumors

A generational study on self-referential advertising — Innovative Marketing, Business Perspectives

The Moderating Effects of Self-Referencing and Relational Self-Construal on Advertising Persuasion — Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking

How personal relevance influences advertising effectiveness — University College London, Department of Psychology

Laughing all the way to the bank: Three ways humour helps brands sell — Marketing Week

Time to get serious about humour in advertising — Kantar

How to get humour right in advertising — Kantar

Humor in advertising can cue more than laughter — Fast Company

Being Funny Pays Off: Let’s Bring Humor Back To Advertising — Forbes Business Council

Is Apple’s “Shot on iPhone” Campaign a Success? — Entri

iPhone 17 Pro and iPhone 17 Pro Max — Apple

iPhone 17 Pro — Wikipedia

When it comes to ads, Apple isn’t playing coy anymore — Digiday

Apple Ads: What you need to know in 2026 — Search Engine Land

Apple apologizes after ad backlash — LinkedIn News

Apple Abruptly Changes Product Marketing Materials Amid Apple Intelligence Controversy — Reddit

Apple Ads Aren’t Cool Anymore. Here’s What I Think Changed — Yahoo

Everyone is roasting Apple’s latest ad campaign. What’s your take? — Reddit

Zoom – Eyecandy Technique — Eyecannndy

A Case Study on Apple’s “Shot on iPhone” Brand Campaign — The Brand Hopper