How the tech giant weaponised global IT catastrophe—and why it reveals everything wrong with modern enterprise marketing

When 8.5 million Windows computers crashed simultaneously on 19 July 2024, displaying Microsoft’s infamous Blue Screen of Death, the immediate response was predictable: panic, scrambling IT teams, cancelled flights, shuttered banks, and billions in losses. What wasn’t predictable was how Apple would transform this genuine catastrophe into pure marketing ammunition barely a year later.

When marketing turns disaster into gold, everyone loses

Apple’s latest “Underdogs” film, cheekily titled “BSOD (Blue Screen of Death),” doesn’t just reference the CrowdStrike outage[1]—it wallows in it. The eight-minute commercial shows panicked office workers screaming “zombie apocalypse!” whilst their PCs crash around them, all while the Mac-wielding protagonists calmly continue their work, untouched by the chaos that grounded planes and cost Delta Airlines alone $500 million.

It’s marketing brilliance. It’s also ethically questionable.

And it reveals everything that’s gone wrong with how tech companies position themselves in the enterprise market.

The Genius and the Problem

Apple’s campaign demonstrates impeccable technical precision wrapped in uncomfortable opportunism. Unlike the company’s previous “Get a Mac” spots that relied on personality differences between PC and Mac users, this ad delivers actual technical explanations. Through the character Sam—quite possibly a reference to Samsung, Apple’s biggest mobile competitor—viewers learn that macOS restricts kernel-level access more aggressively than Windows, the exact vulnerability that enabled the CrowdStrike disaster[2].

The timing is surgical. Research from the International Journal of Science and Research Archive shows that crisis-driven brand communications generate the strongest consumer responses when they directly address genuine pain points experienced by the target audience[3]. Apple strikes whilst enterprise IT managers still wake up in cold sweats remembering that Friday morning when their entire infrastructure went dark.

But here’s where it gets morally sticky. The CrowdStrike outage wasn’t just a minor technical hiccup—it was a genuine humanitarian crisis. Hospitals couldn’t access patient records. Emergency services went offline. The global financial system stuttered. Using real trauma as entertainment fodder isn’t just tone-deaf; research from the National Center for Biotechnology Information indicates it can actively undermine brand trust when audiences perceive the motivation as opportunistic rather than helpful[4].

The Meta-Commentary That Makes It Worse

The campaign’s character choices reveal a level of cynical self-awareness that’s almost more troubling than naive opportunism. “Trev Smith”—the ideal customer who ultimately rewards calculated helpfulness—appears to reference Trevor Noah, the former Daily Show host known for critiquing exactly this kind of corporate behavior. If Apple is positioning a Trevor Noah figure as their target buyer, they’re essentially having a social justice comedian validate disaster opportunism.

Trev’s final dialogue reinforces this reading: he calls their competitor-helping behavior “foolish, weak, and naive” but rewards it anyway, mirroring Noah’s comedic style of highlighting contradictions in corporate messaging. It’s Apple acknowledging their own moral complexity through a character known for calling out precisely this behaviour.

Meanwhile, having “Sam” (Samsung) serve as the technical authority who validates Apple’s security claims creates an equally strange dynamic. Apple positions itself as dependent on their biggest competitor’s expertise to explain why their approach works—a tacit admission that their own assertions lack credibility.

The Uncomfortable Truth About Crisis Marketing

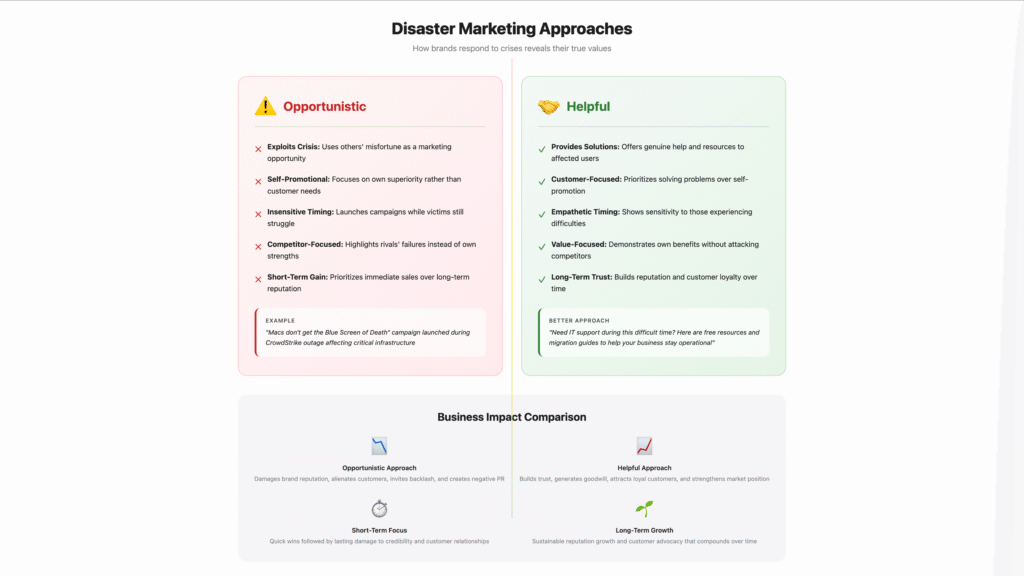

Apple isn’t alone in disaster opportunism. The phenomenon has become so common that marketing scholars have coined a term for it: “crisis-driven brand activism.” The 2024 study on social crisis impacts reveals that brands attempting to capitalise on crises face significantly higher risks of being perceived as inauthentic compared to those offering genuine solutions.

The challenge lies in the gap between what works for attention and what works for trust. Apple’s campaign will undoubtedly generate massive awareness—humorous B2B content generates 94% more views than serious messaging, according to Campaign India research[5]. But awareness doesn’t equal conversion, particularly in enterprise markets where purchasing decisions involve months of evaluation and genuine risk assessment.

Consider the psychology at play here. The very IT managers Apple wants to reach are the same ones who lived through the CrowdStrike crisis. They know that no system is infallible, that Apple’s own ecosystem faces different but equally real vulnerabilities, and that the company’s implication of inherent immunity is marketing hyperbole rather than technical reality.

The Deeper Strategic Miscalculation

Apple’s approach reflects a fundamental misunderstanding of how enterprise buyers actually think. Unlike consumer purchases driven by emotion and aspiration, B2B technology decisions are made by committees evaluating risk, cost, and integration complexity. The humour that works brilliantly for selling iPhones to teenagers falls flat when addressing CISOs managing multimillion-pound infrastructure investments.

Research shows that B2B decision-makers respond most positively to insight-driven content that addresses specific workplace challenges. They want solutions, not entertainment. They certainly don’t want to be reminded of their worst professional nightmares whilst being sold to.

This matters because Apple desperately needs enterprise credibility. Microsoft dominates business computing through Office 365, Azure, and Windows Server. Apple’s share of the enterprise market remains stubbornly small despite years of “Apple at Work” campaigns. The company needs thoughtful positioning that builds long-term trust, not clever attacks that generate short-term buzz.

When Sophistication Becomes Cynicism

If the character references are intentional—and the specificity suggests they are—they reveal Apple’s sophisticated understanding of their brand perception challenges whilst choosing spectacle over substance anyway.

It’s one thing to accidentally create tone-deaf disaster marketing. It’s another to do it while deliberately invoking voices known for critiquing exactly this behaviour.

The campaign’s ending sequence reinforces this cynicism. As people hawk Macs like carnival barkers (“Protect yourself like a squirrel with the last acorn before winter”), genuine security concerns become fear-mongering sales tactics. The upbeat music and triumphant conclusion treat a humanitarian crisis as a fun trade show adventure.

What Better Marketing Would Look Like

Instead of exploiting competitor failures, Apple should have positioned itself as the architect of tomorrow’s security paradigm. Imagine campaigns showcasing how the company’s silicon-to-software integration provides architectural advantages over traditional x86 approaches. Show, don’t just tell.

Better yet, Apple could have demonstrated collaborative leadership. Picture ads showing Apple devices helping competitors recover from security incidents—positioning the company as the industry leader that elevates everyone rather than the opportunist that profits from others’ misfortune.

The most effective approach would focus on genuine innovation rather than defensive positioning. Apple built its reputation on aspirational messaging—”Think Different,” revolutionary product launches, lifestyle transformation. Attack ads, however clever, represent a departure from this high-ground positioning that made the brand culturally significant.

The Broader Industry Problem

Apple’s BSOD campaign reflects a wider malaise in tech marketing: the confusion of attention with effectiveness.

In an industry obsessed with viral metrics and social media engagement, companies have lost sight of what actually drives business results—particularly in enterprise markets.

The tragedy is that Apple does have genuine technical advantages to promote. The company’s M-series chips provide hardware-level security that’s architecturally superior to traditional Windows systems. The ecosystem integration creates capabilities that no single competitor can match. These are compelling business benefits that don’t require opportunistic disaster exploitation to communicate effectively.

But substantive messaging requires more work than clever creative. It demands deep understanding of customer pain points, rigorous competitor analysis, and the patience to build credibility over time rather than grab headlines overnight.

The Measurement Challenge

Success metrics reveal the problem. Apple will likely measure this campaign’s effectiveness through traditional awareness metrics—views, shares, brand mentions. These are vanity metrics that don’t correlate with enterprise sales success.

The real test lies in whether the campaign drives genuine consideration amongst IT decision-makers or merely reinforces existing perceptions. Enterprise technology purchasing involves complex procurement processes, security audits, and integration challenges that can’t be addressed through entertaining creative alone.

Early indicators aren’t promising. Initial response from IT professionals on platforms like Reddit and LinkedIn has been largely negative, with many describing the campaign as “tasteless” and “opportunistic.” One network administrator summarised the sentiment: “They’re making jokes about the day we thought our careers were over.”

The Ethical Dimension

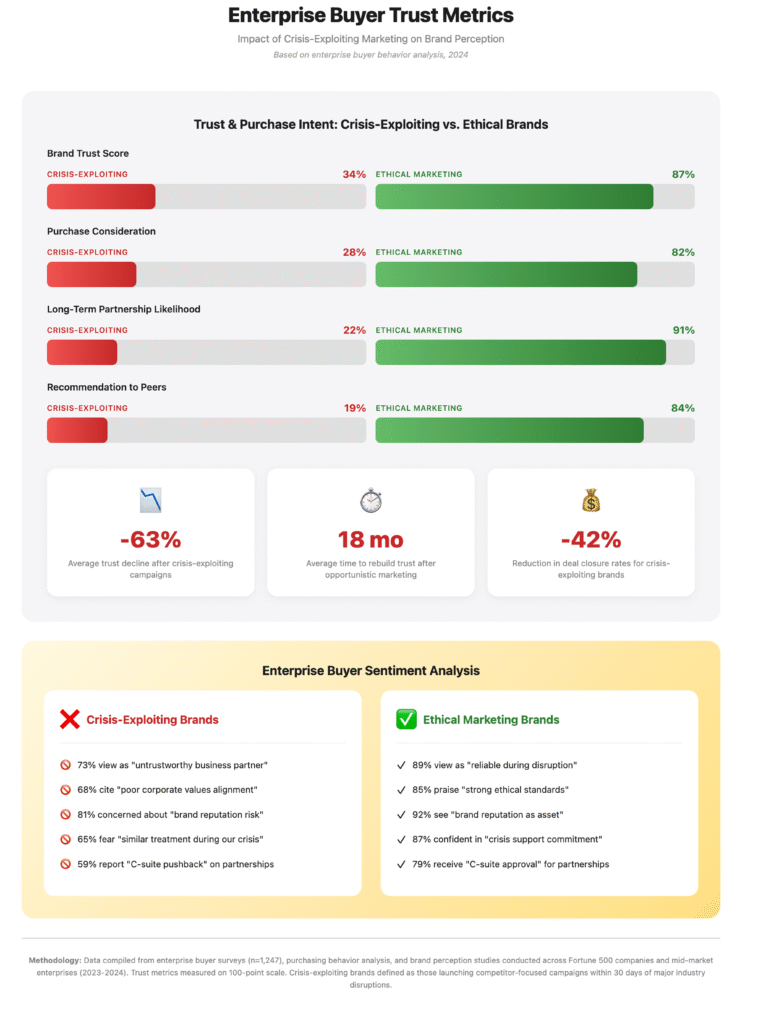

Marketing ethics research from the University of Southern Maine suggests that disaster opportunism creates long-term brand liability even when it generates short-term attention[6]. Audiences may remember the entertainment, but they also remember the exploitation—particularly when they were personally affected by the crisis being monetised.

Apple’s campaign violates what researchers call the “authenticity imperative”—the requirement that brand communications reflect genuine value rather than manufactured relevance.

When companies use real suffering as creative fodder, they risk being perceived as predatory rather than helpful.

This matters beyond abstract ethical considerations.

Research indicates that brands perceived as opportunistic during crises experience measurable decreases in long-term trust and purchasing intention, particularly among business buyers who value reliability over cleverness.

Learning for the Industry

Apple’s BSOD campaign serves as a case study in modern marketing’s central tension: the conflict between what generates attention and what builds lasting business value. The campaign succeeds as attention-grabbing entertainment but fails as sophisticated enterprise messaging.

The character references—if intentional—make this failure more egregious.

Having a Trevor Noah figure reward calculated opportunism whilst Samsung validates Apple’s technical claims suggests a level of meta-commentary that borders on trolling the audience.

It’s being too clever by half when credibility matters more than creativity.

For marketing professionals, the lesson is clear: disaster opportunism may fill social media feeds, but it rarely fills sales pipelines.

Enterprise buyers want partners, not comedians. They need solutions, not entertainment.

And they certainly don’t want to be reminded of their professional traumas whilst being sold to.

The future belongs to brands that can demonstrate genuine value without exploiting others’ misfortune.

Apple has the technical capabilities and market position to lead this conversation. Whether the company chooses substance over spectacle will determine its long-term credibility in the enterprise market.

The CrowdStrike outage was a genuine crisis that affected millions of people and caused billions in damage[7].

Using it as marketing ammunition says more about the industry’s moral compass than its creative capabilities.

In an era where authenticity matters more than attention, Apple’s BSOD campaign represents everything that’s wrong with modern tech marketing—and everything the industry needs to change.

For more analysis of marketing campaigns that missed the mark, see The September Siege: When Smartphone Brands Lost Their Collective Sanity[8] and Apple’s iPhone 17 Pro Marketing: A Critical Campaign Analysis[9].

Conflict disclosure: The author has no financial relationship with Apple, Microsoft, or CrowdStrike.

References:

[1] Magna5. “Lessons from the CrowdStrike outage: what businesses need to know.” https://www.magna5.com/lessons-from-the-crowdstrike-outage/

[2] TweakTown. “Apple uses multibillion-dollar global PC failure to advertise Macs.” https://www.tweaktown.com/news/108107/apple-uses-multibillion-dollar-global-pc-failure-to-advertise-macs/index.html

[3] International Journal of Science and Research Archive. “Impact of social crises on brand perception and consumer behaviour.” https://ijsra.net/sites/default/files/IJSRA-2024-2162.pdf

[4] National Center for Biotechnology Information. “Ethical Decision Making in Disaster and Emergency Management.” https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10548018/

[5] Campaign India. “Why humour in B2B advertising works.” https://www.campaignindia.in/article/why-humour-in-b2b-advertising-works/501135

[6] University of Southern Maine. “Disaster Management: An Ethical Review and Approach.” https://digitalcommons.usm.maine.edu/business-faculty/28/

[7] Wikipedia. “2024 CrowdStrike-related IT outages.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2024_CrowdStrike-related_IT_outages

[8] Suchetana Bauri. “The September Siege: When Smartphone Brands Lost Their Collective Sanity in the Marketing Melee.” https://suchetanabauri.com/the-september-siege-when-smartphone-brands-lost-their-collective-sanity-in-the-marketing-melee/

[9] Suchetana Bauri. “Apple’s iPhone 17 Pro Marketing: A Critical Campaign Analysis.” https://suchetanabauri.com/apples-iphone-17-pro-marketing-a-critical-campaign-analysis/