Yesterday, I published my analysis of Google’s timeline problem—how Aniket’s story compressed “2-3 weeks from zero coding to Android app winner,” creating a 92% gap between marketing promise and educational reality.

That piece focused on one video. One promise. One timeline problem.

However, it raised a question I couldn’t shake: Is this how these companies actually teach developers? Or just how they market to them?

Consequently, I spent the past 24 hours doing something obsessive: watching both Microsoft Developer and Google for Developers channels closely. Not cherry-picking viral videos. Not hunting for gotchas. Just observing what they publish, how they frame it, who presents it, and what they promise.

I analysed six videos published between 13-16 January 2026—three from each company. Not promotional content. Technical tutorials. The stuff developers actually watch when they’re trying to learn, not when they’re being sold to.

What I found surprised me.

First, the timeline compression problem I documented yesterday? It doesn’t exist in their educational content. Both companies are reasonably honest about constraints, costs, and complexity when their education teams control the message.

But something else emerged—something more interesting than “one company good, one company bad.”

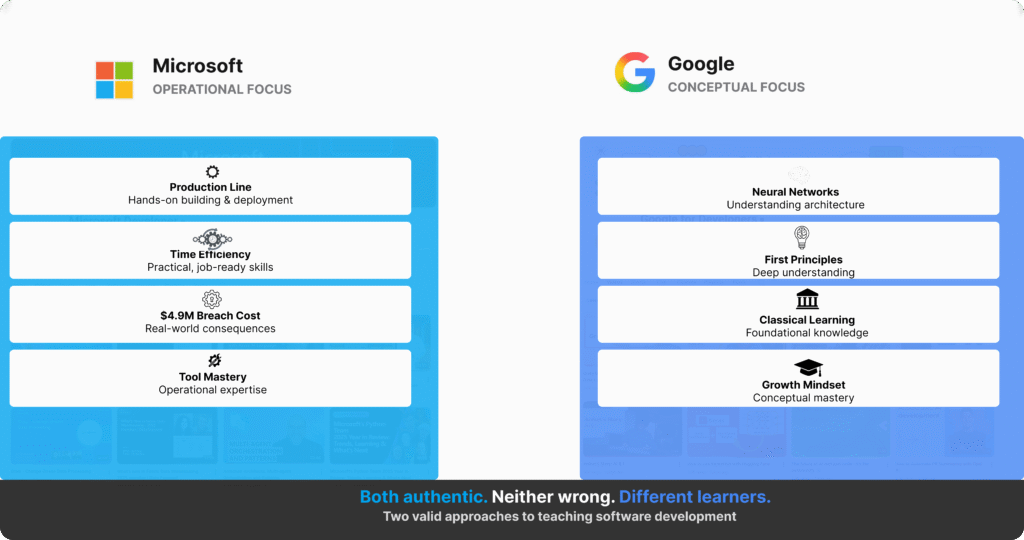

Specifically, Microsoft and Google teach from fundamentally different philosophies about what developers need, how they learn best, and which outcomes matter most. Neither is dishonest. Neither is wrong. Nevertheless, they serve completely different types of learners—and understanding which philosophy fits which developer reveals what authentic developer education actually looks like.

“Both companies teach from fundamentally different philosophies about what developers need and how they learn best. Microsoft optimises for operational realism. Google optimises for conceptual foundations.”

What I watched: six videos, one week, two philosophies

Over past 24 hours, I tracked every video both channels published between 13-21 January 2026. Here’s what stood out:

Microsoft Developer (13-16 January)

Protect sensitive data with Azure AI Language PII Redaction (4m 14s, published 13 Jan)

What it teaches: Detecting and masking personally identifiable information across text, documents, speech transcripts

Framing approach: Opens with “$4.9M average data breach cost,” explicitly discusses GDPR/HIPAA compliance, shows customisation options, states “current limitations”

DiskANN: Vector indexing in Azure SQL and Fabric SQL (17m 38s, published 15 Jan)

What it teaches: Approximate nearest neighbour search in databases, CPU vs. I/O trade-offs

Framing approach: “Creating a vector index takes quite a while,” “we might not return all the results you expect,” explicit public preview constraints

Build Powerful AI Apps for under $25 (Budget Bytes launch) (48s teaser, published 15 Jan)

Key promise: Transparent cost breakdowns, realistic timelines (“a few hours”), concrete pricing (“$10 a month”)

Google for Developers (recent uploads):

Introduction to JAX concepts (10m 02s)

What it teaches: Functional purity, immutability, explicit state management, JIT compilation

Framing approach: Opens with “mastering JAX requires a significant shift in your mental models”

InovCares: Health Connect API (Under 5m)

What it teaches: Integrating Health Connect API for maternal health monitoring

Framing approach: Founder Mo’s personal story (sister and aunt died during childbirth) before any technical details

Keras Turns 10: A decade of deep learning (39m 56s, published 16 Jan)

What it teaches: Framework design philosophy, community-driven development, “progressive disclosure of complexity”

Framing approach: Six minutes explaining Greek mythology etymology of “Keras” (gate of horn vs. gate of ivory)

After watching all six—some multiple times—a pattern crystallized that had nothing to do with “good vs. bad” and everything to do with what each company optimises for.

Pattern one: Microsoft teaches like you’re shipping tomorrow

Operational problems, not conceptual frameworks

The first thing you notice watching Microsoft Developer for a week: every video assumes you have a production problem to solve today.

When the PII Redaction video opens, there’s no inspirational framing. No “imagine a world where…” No “what if you could…”

Instead: “We know that a costly and permanent challenge in our world today is handling sensitive personally identifiable information in your data to ensure user and industry trust.”

Then immediately: specific research citation (Identity Theft Resource Center 2023), specific cost figure (IBM Security $4.9M average breach), specific regulatory requirements (GDPR, HIPAA named explicitly).

Consequently, by 30 seconds in, a developer watching this understands:

- Why this problem matters operationally (breach costs)

- What compliance requirements they must satisfy (specific regulations)

- What the business impact is if they don’t solve this (millions in damages)

No conceptual setup. No paradigm explanation. Instead, it goes straight to: here’s the operational problem you’re facing.

Customisation options, not theoretical possibilities

The demo follows the same pattern. Not “here’s what’s conceptually possible,” but rather “here’s what works, here’s what you can customise, here’s what you should know”:

- Entity types you can redact (SSN, addresses, person names—specific)

- Masking styles you can choose (asterisks, custom characters, entity type labels—concrete options)

- Values you can exclude from redaction (example: “take out the name Matteo Gomez”—actual use case)

- Synonyms you can add for vocabulary the model doesn’t recognise by default—practical workaround

At 2m 40s: “To address the complexities of diverse natural language scenarios, our service offers three different modalities. Text PII for raw unstructured text… Conversational PII for speech transcripts… Native DocPII for document files like Word or PDF.”

Crucially, this isn’t teaching a concept (what is PII?). Rather, it’s teaching a decision tree: which modality for which production scenario.

At 4m 01s: “Ready to explore? Head over to the Azure AI Foundry portal to try these services yourself.”

Specific next step. Specific platform. Immediate action.

Honest about time costs and limitations

The DiskANN vector indexing video exemplifies this approach even more starkly.

Developer David walks through creating vector search on 100,000 property records. At 6 minutes in, he’s mid-demo and stops:

“Creating a vector index takes quite a while because creating the graph is a complex process. So I’ll just skip this operation.”

He doesn’t hide the time cost. In fact, he explicitly acknowledges it—then skips it in the demo because the video isn’t about watching loading bars. Rather, it’s about understanding what you’re getting into operationally.

Later, showing indexed search results: “We might not return all the results you expect. That’s why developers need to use a different function called vector_search instead of vector_distance. Why we made this choice is because it is an approximate search. We cannot guarantee it.”

Furthermore, he explains why it’s approximate (no sorting logic in high-dimensional vector space), what trade-offs that creates (speed vs. exhaustiveness), and when you should accept those trade-offs (operational databases prioritising concurrent queries over exhaustive scans).

At 12m 56s: “There are some gotchas… That is going to be removed, but for now if people want to start to play with this they need to be aware.”

He lists the gotchas. Current public preview limitations. What doesn’t work yet. What will change.

This is teaching for developers who will put this in production tomorrow. The priority isn’t conceptual elegance—it’s operational preparedness. Costs, constraints, gotchas, when things break, what to avoid.

Pattern two: Google teaches like you’re building mental models

Conceptual confusion that needs resolving

Switch to Google for Developers, and the framing is radically different.

The JAX tutorial opens: “Are you exploring JAX and trying to understand what all these new terms mean? How are ‘functional purity,’ ‘immutability,’ and ‘explicit state management’ going to help your machine learning model? And what’s all the chatter about JIT even mean?”

The framing is conceptual confusion that needs resolving—not operational problems that need solving.

Accordingly, the next four minutes don’t teach you how to use JAX. Instead, they teach you why JAX is designed the way it is:

“We’re using the word ‘pure’ here to describe a function that always does the same thing for the same set of inputs, no matter what. No, seriously, no matter what. Have you ever modified a variable that lives outside of the function? Not pure. Ever read the value of something outside the function, like, say, a global parameter? Sorry. Not pure.”

This is teaching a paradigm shift. Not “here’s the syntax” but “here’s how you need to think differently.”

This conceptual-first approach mirrors what I documented in Anthropic’s Claude marketing strategy—prioritising understanding over immediate utility, building mental models before teaching implementation.

Then: “That seems awfully restrictive, right? It is, but it’s also the price to be paid for having blazing-fast performance. Because functions can’t do anything outside of exactly what is inside, JAX can optimise your program way more, enabling it to run fast and scale well.”

By the time the video reaches JIT compilation (7m 31s), PRNG key management (4m 50s), and control flow limitations (8m 07s), you understand the underlying paradigm that makes all these constraints necessary.

As a result, you’re not memorising “use jax.lax.cond for conditionals.” Rather, you’re understanding why runtime-dependent conditionals break tracing, and therefore when you need specialised control flow.

Human stories before technical implementations

The InovCares video follows the same pattern—but applied to motivation rather than technical paradigms.

The first 40 seconds establish human context: “My older sister and aunt both passed away during childbirth. This highlighted the critical issue of maternal health disparities, particularly among minority mothers.”

Only after establishing why this matters personally and socially does Mo explain the technical integration: “InovCares partnered with Google to integrate the Health Connect API, allowing mothers to automatically track their steps and sleep using Google Fitbit.”

The technical implementation is secondary to the human problem it solves. Consequently, the video teaches why you’d build this before how you’d build this.

Design philosophy as teaching material

The Keras 10-year anniversary conversation epitomises this philosophy.

François Chollet, Keras founder, spends six full minutes (6m 05s – 12m 00s) explaining why the framework is named “Keras”:

“In Greek literature, you have this idea that dreams are caused by spirits… There are two kinds of dream spirits. There’s the false ones that give you a vision of the future that will not be realised. And there’s the true dream spirits that give you a prophetic vision… The false dream spirits come to Earth through a gate of ivory, and the true dream spirits come to Earth through a gate of polished horn. Keras, the gate of horn, is the portal through which a true vision of the future to be realised.”

Is this necessary to use Keras? No.

Does it teach you the design philosophy that shaped every API decision over ten years? Absolutely.

Later (23m 50s), discussing API design: “Simple things should be super easy. Anything that most people are going to want to do should be just a couple lines of code effectively. And anything that is very complex, very advanced, should be possible through a path that is incremental. There should not be a cliff where you’re like, ‘OK, until now it was easy, but now I need to customise this thing, so I have to throw away this entire pile of code and rewrite it from scratch.'”

This isn’t teaching syntax. Rather, it’s teaching how to think about API design—which makes you better at evaluating all frameworks, not just Keras.

The insight after 24 hours: neither philosophy is wrong

Microsoft optimises for Builders—developers who learn best through immediate application. Google optimises for Architects—developers who learn best through conceptual models first.

Two learning modes, not two personality types

After watching both channels obsessively for 9 hours straight, here’s what became clear:

Microsoft optimises for Builders—developers who learn best through immediate application, want to ship code today, encounter problems tomorrow, learn concepts as constraints force them.

Google optimises for Architects—developers who learn best through conceptual models first, want to understand paradigms deeply, then apply them across contexts.

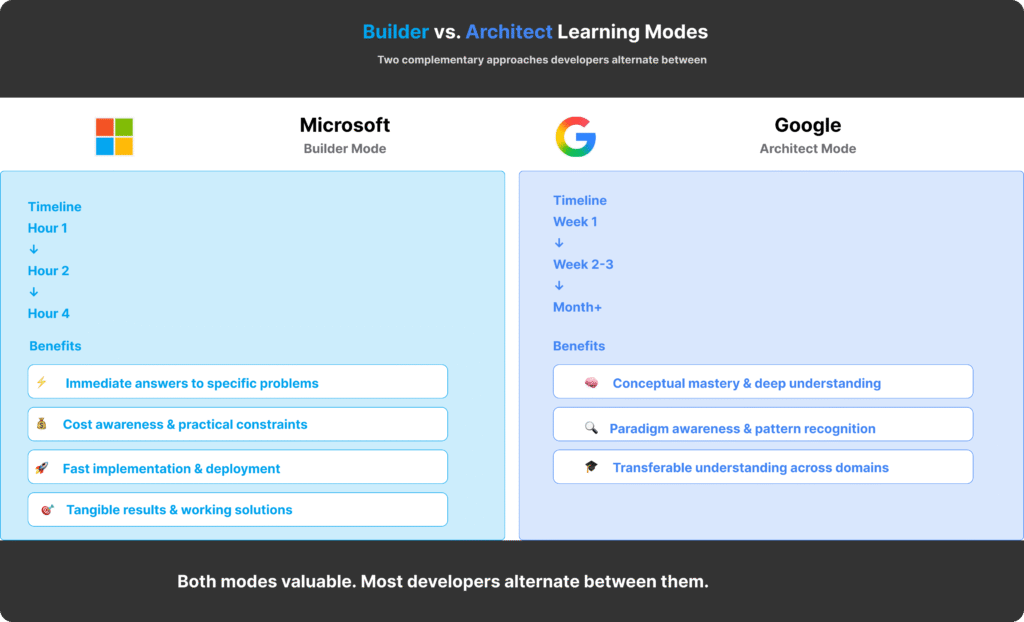

Research on developer learning strategies shows these aren’t personality types—they’re learning modes most developers alternate between depending on context.

This distinction parallels what I’ve written about “slow AI versus fast AI”—sometimes you need immediate answers (Builder mode, fast AI), sometimes you need deep understanding that takes 45 minutes to develop (Architect mode, slow AI). Both have value; neither is universally “better.”

When Builder mode serves you

When you’re in Builder mode (production deadline, operational problem, need solution now):

Microsoft’s approach serves you brilliantly. For example:doesn’t work yet

- “Here’s the problem scale ($4.9M breach cost), here’s the solution (PII redaction), here’s what you customise (entity types, masking), here’s where to try it (AI Foundry portal)”

- Immediate next step at 4m 01s

- You can ship tomorrow

When Architect mode serves you

When you’re in Architect mode (learning new paradigm, evaluating framework choices, building transferable understanding):

Google’s approach serves you brilliantly. Specifically:

- “Mastering JAX requires a significant mental model shift”—frontloaded honesty

- Explains why functional purity enables optimisation, how that constraint shapes everything else

- You build adaptable mental models applicable beyond just JAX

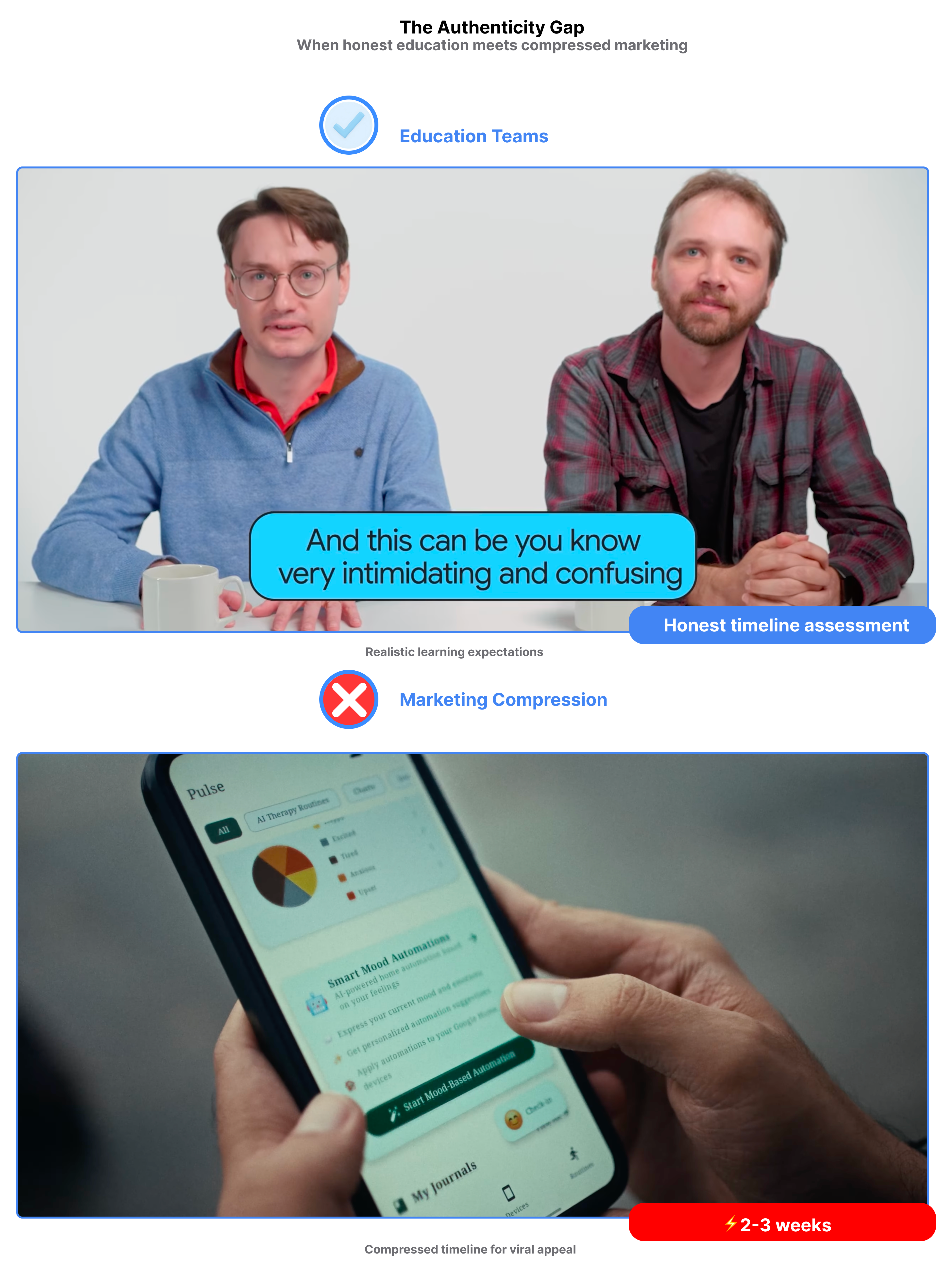

The problem documented in yesterday’s Aniket analysis wasn’t “Google’s education team is dishonest.”

Rather, it was “Google’s marketing team compressed timelines (‘2-3 weeks’) that contradict educational reality (‘2-3 years for most developers’).”

The authenticity gap: education vs. marketing

What education teams acknowledge

Here’s what watching both channels for a week revealed:

When education teams control messaging, both companies are reasonably honest:

Microsoft explicitly states:

- “Creating a vector index takes quite a while” (DiskANN, 6m 06s)

- “Current limitations in public preview” (DiskANN, 12m 56s)

- “We might not return all the results you expect” (DiskANN, 7m 36s)

- Budget Bytes promises “a few hours” for app development—not minutes

Similarly, Google explicitly states:

- “Mastering JAX requires a significant shift in your mental models” (JAX, 1m 03s)

- Keras adoption involved years of community iteration (Keras 10, 10m 59s – 15m 46s)

- François on Keras 3 timeline: “Two months” for experienced team, not beginners (Keras 10, 15m 46s)

This kind of honesty—acknowledging constraints, stating realistic timelines, distinguishing expert from beginner capabilities—is what I’ve called “authenticity marketing” elsewhere. It works because it manages expectations rather than inflating them.

Where marketing compresses timelines

The timeline compression I documented yesterday—”2-3 weeks from zero coding to Android app winner”—didn’t come from these technical tutorials.

Instead, it came from promotional content optimising for virality.

When Microsoft teaches DiskANN, they say “this takes quite a while.”

When Google teaches JAX, they say “requires significant mental model shift.”

Yet when Google’s marketing showcases Aniket, they compress to “2-3 weeks.”

Consequently, the gap is between education departments being honest and marketing departments being aspirational.

This pattern isn’t unique to tech companies. As I documented in September’s smartphone marketing siege, marketing departments across industries compress timelines and inflate capabilities when competing for attention—whilst product teams remain grounded in reality.

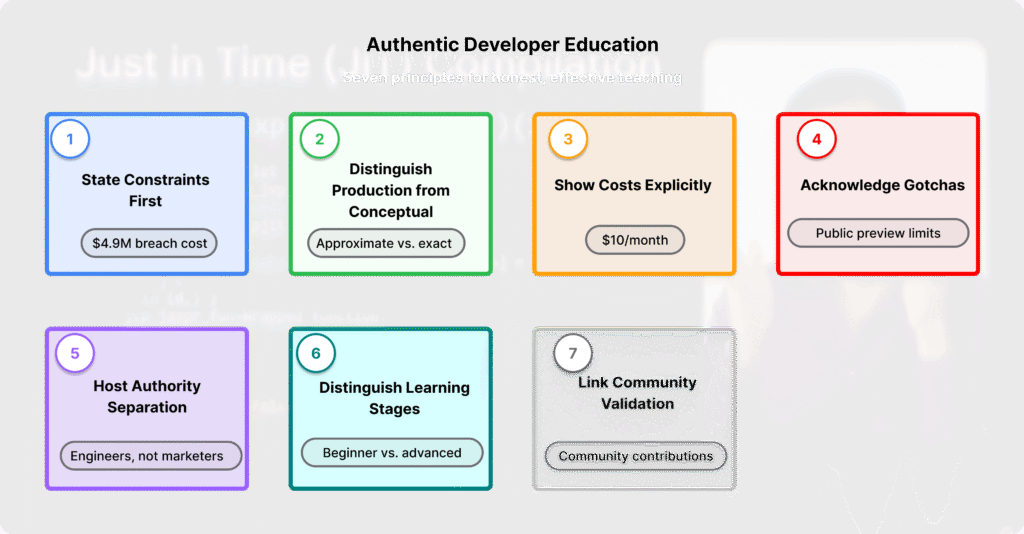

Seven principles of authentic developer education

After analysing these six videos, here’s what authentic teaching looks like—regardless of whether you’re optimising for Builders or Architects:

1. State constraints before capabilities

Microsoft (PII, 0m 21s): “Identity Theft Resource Centre research in 2023 reports sensitive personal information remains the most common type of data breach. IBM Security found the global average cost of a data breach in 2024 was $4.9 million.”

This establishes problem scale before solution.

Google (JAX, 1m 51s): “That seems awfully restrictive, right? It is, but it’s also the price to be paid for having blazing-fast performance.”

Similarly, this acknowledges functional purity restricts what you can do before explaining why that restriction creates value.

2. Distinguish “production-ready” from “conceptually possible”

Microsoft (DiskANN, 7m 36s): “This is an approximate search. We cannot guarantee it. We might not return all the results you expect. That’s why developers need to use a different function called vector_search instead of vector_distance.”

This explicitly separates exact search (conceptually correct) from approximate search (production-optimised).

This “show, don’t tell” approach echoes Anthropic’s Claude Sonnet 4.5 launch strategy—demonstrating actual capabilities (gaming, software creation, browser automation) rather than just describing them abstractly.

Google (Keras, 15m 46s): “We went from Keras 3 as a concept to shipping in about two months. We were really locked in, all working together. I was shipping several thousands of lines of code per day.”

François describes an experienced team timeline—not beginner, not even intermediate developer timeline.

3. Show costs explicitly—financial and cognitive

Microsoft (Budget Bytes, 0m 23s): “How to build an AI agent with your data securely using Copilot Studio for like $10 a month.”

Not “affordable”—actual number. You can budget.

Google (JAX, 1m 03s): “Mastering JAX requires a significant shift in your mental models.”

Not “easy”—honest about cognitive cost. You can prepare.

4. Acknowledge what doesn’t work yet

Microsoft (DiskANN, 12m 56s): “There are some gotchas… That is going to be removed, but for now if people want to start to play with this they need to be aware.”

Public preview limitations stated upfront.

Google (JAX, 8m 07s): “If-else statements and loops that depend on runtime values of JAX arrays within a jitted function can lead to errors or unexpected behaviours… You’ll need to use jax.lax.cond or jax.lax.while_loop.”

Normal Python control flow breaks. Specialised functions required.

5. Separate host authority from marketing authority

Microsoft hosts: Sr. Cloud Solution Architects, product engineering teams, developers who’ve shipped production code using these tools

Google hosts: Developer advocates (Yufeng Guo), founders (François Chollet), community leaders (Mo from InovCares)

Neither uses “VP of Marketing” as tutorial hosts. Instead, technical authority comes from people who’ve built things.

6. Distinguish learning stages explicitly

Google (Keras, 24m 59s): “Simple things should be easy. Advanced workflows should be possible through incremental paths.”

This acknowledges beginner needs (easy entry) and advanced needs (customisation) differ.

Microsoft (Budget Bytes, 0m 17s): “Whether you’re a student, a startup, a small business, or a seasoned developer, Budget Bytes is your guide.”

Explicitly names different learner types.

7. Link education to community validation

Google (Keras, 21m 11s): “Most of the best Keras team members over the years have been people from the community. It’s always a good idea to recruit your users.”

Teaching isn’t top-down. Rather, community contributions shape the framework.

Microsoft (DiskANN): Uses real community-contributed database (Jose’s 100,000 fake property records) for demo. Acknowledges external contribution explicitly.

What a week of observation taught me

Education teams vs. marketing teams

When I started this, I expected to find more timeline compression problems like Aniket’s story.

What I found instead: both companies’ education teams are doing honest work. They acknowledge constraints. They state timelines realistically. They distinguish production-ready from conceptually possible.

However, the dishonesty emerges when marketing departments compress those timelines to compete for attention—promising Builder outcomes (ship in days) using Architect methods (master paradigms first), or vice versa.

When each approach works brilliantly

Microsoft’s operational tutorials work brilliantly if you’re in Builder mode: production deadline, need solution now, want concrete next steps.

Similarly, Google’s conceptual tutorials work brilliantly if you’re in Architect mode: evaluating frameworks, building transferable understanding, learning new paradigms.

The problem isn’t the teaching. Rather, it’s when marketing promises don’t match educational reality.

Authentic developer education: State constraints before capabilities. Distinguish production-ready from conceptually possible. Show costs explicitly—financial and cognitive. Acknowledge what doesn’t work yet.

The trust question

After publishing yesterday’s analysis of the Aniket timeline problem, several readers asked: “So which company is more honest?”

After watching both channels obsessively for the past 24 hours, my answer: Both education teams are honest. Marketing teams, however, sometimes aren’t.

Consequently, the real question isn’t “Microsoft vs. Google.”

It’s “Are we letting education teams stay honest—or are we forcing them to compress timelines to match marketing’s promises?”

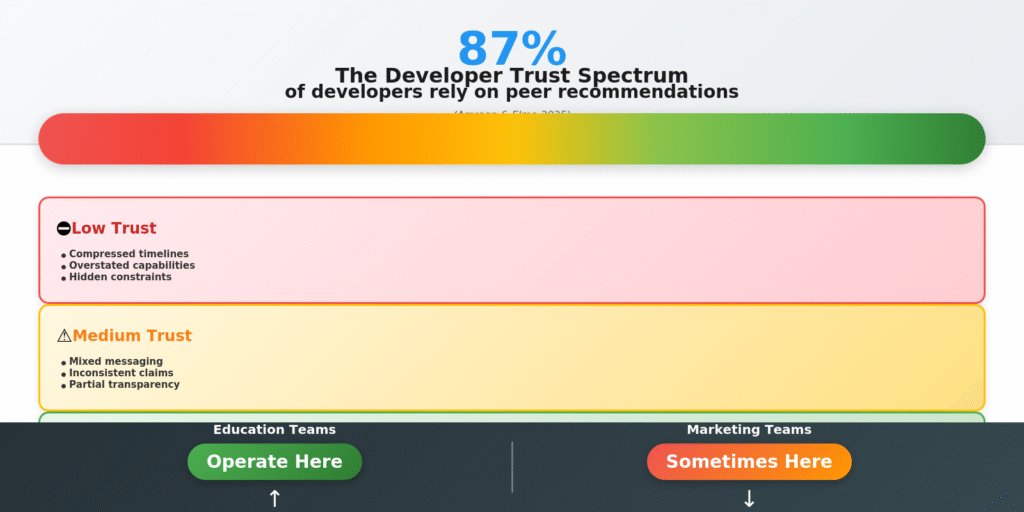

Because when education stays honest, developers learn. In contrast, when marketing compresses timelines, developers lose trust. Moreover, in an industry where 87% of developers rely on peer recommendations over corporate claims, trust is the only currency that matters.

Footnotes & sources

- Published context: This article follows my analysis published 21 January 2026: “The Timeline Problem: What Google’s Viral Developer Story Gets Wrong About Learning to Code”

Videos analysed (13-21 January 2026 observation period)

Microsoft Developer

- Protect sensitive data with Azure AI Language PII Redaction, 13 January 2026 (4m 14s)

- DiskANN: Vector indexing in Azure SQL and Fabric SQL, 15 January 2026 (17m 38s)

- Build Powerful AI Apps for under $25 (Budget Bytes launch), 15 January 2026 (48s)

Google for Developers

- Introduction to JAX concepts (10m 02s)

- InovCares: Maternal health with Health Connect API (Under 5m)

- Keras Turns 10: A decade of deep learning, 16 January 2026 (39m 56s)

Supporting research

- IBM Security, “Cost of a Data Breach Report 2024”

- Identity Theft Resource Centre, “2023 Annual Data Breach Report”

- Amraan & Elma Research, “TOP 20 Developer Marketing Statistics 2025”

- Draft.dev, “How to Write Technical Tutorials That Developers Love”, November 2025

- Jenkov Tutorials, “Developer Learning Strategies”

- Algocademy, “Why Watching Tutorials is Not Learning”, December 2024

- “Why software developers don’t buy the hype”, September 2025